Thursday, 22 December 2016

Goodbye - for now

Well, we tried. We tried to warn you that Brexit was far, far more likely than people said. We tried to wave the flag about the unknown-but-mounting likelihood of a new age of rage and danger. It wasn't enough. In a year when analytical approaches, data-driven techniques, the art of using evidence and even reason itself were in retreat throughout, we tried to hold tight to just those methods. It didn't always work. But we hope you were informed, enlightened, and perhaps even sometimes moved by what you read here. We'll be back on Monday 16 January, to track the French and German elections, ongoing Brexit negotiations, Labour's gloomy travails, and the first days of the Age of Trump. Don't you dare miss it. But in the meantime - look after yourselves, and enjoy your holidays.

Sunday, 18 December 2016

Welcome to the age of the gangsters

Now you know all about Donald Trump (above) by now. He says that he could shoot someone down in the street, and he'd still be popular. He says he might not respect election results. He flirts with torture. He threatens to jail his main opponent (before saying he won't). He singles out individual journalists and trade union leaders for verbal harangues, both on social media and in person. He calls on the Russian state to hack rival politicians. He praises the autocracy of Vladimir Putin. He tries to cave in the businesses of companies - from Boeing to Vanity Fair - who happen to disagree with him. He cajoles. He wheedles. He shouts. He bellows. He stamps his feet.

There's a good word for this, and before you say, it isn't fascism: it's gangsterism. Mr Trump lacks the private militia, the uniform-wearing - and if everyone's really honest, the will to total power - that gets you a really paid-up season ticket to the fascist club. He's not interested in ideology, particularly - though as mid-twentieth century fascists' grip on ideological consistency was often deliberately slippery, that difference on its own doesn't matter all that much. So. He is a bully, a narcissist and a sociopath, but reality seems a bit more prosaic than all the epithet-slinging that Democrats will (understandably) subject him to. The President-Elect is an almost perfect reflection of and vessel for the fury of older white men in the Rustbelt. He feeds off the power of that anger all the time: and as such, he often just indulges himself in an endless stompabout designed to stoking both his ego and the self-image of his voters. He must be the outsider pitched against the know-it-all insiders. He has no choice. History has veered off, somehow, into burn-it-all down biker gang nihilism, and if striking a pose that looks very much like a fist with a wig on top isn't to your taste, you'd best look away now.

While Mr Trumps stamps around as deafeningly as possible, it just so happens that both himself and his nearest and dearest will become just as rich as they possibly can. His daughter sat in on his first summit with the Japanese, all the better to assist with her business interests in that country. Mr Trump's hotel in Argentina suddenly got clearance when he was elected (though any outright collusion has been denied). He has hundreds, perhaps thousands, of conflicts of interest all over the globe - including, reportedly, in Taiwan, site of his first confrontation with Beijing. He's not going to put all his investments in a blind trust, whatever anyone says. Perhaps he'll do very tidily out of the wall-and-fence on the Mexican border. No doubt his Cabinet of billionaires will profit very nicely out of the likely economic boom of the next two or three years, as Mr Trump smashes through all the deficit limits and budget caps that Republicans used to say they cared about.

Now, we'll grant you that this is leagues less sinister than Mussolini's take-over in Italy (for instance), but it's still not great. Most dangerously, it's a recipe for confrontation between the USA and Russia that could boil over in all sorts of frightening ways. Bear in mind that most wars are caused by miscalculation about the extent to which rivals and opponents will fight to protect their interests. The first Iraq War of 1990-91 began when a US official erroneously gave Saddam Hussein the impression that the Americans might not protect Kuwaiti independence, for instance. Mr Trump has already given out by far the most dangerous signals of his short time in public life: that he is not altogether keen on NATO, and that he might not defend NATO states (such as Russia's Baltic neighbours) if they don't pay their way. John Kennedy said of the Soviet leadership in his inauguration that the US 'dare not tempt them with weakness'. That's exactly what Mr Trump has done already. He's sown the seeds of future miscalculation, and bigly. No doubt the Russian cyber-attacks, misinformation and nativist propaganda are already lined up ready to go.

When and if Mr Putin betrays The Donald - over Iran, perhaps, or over the Baltic States, or by continuing to meddle in American domestic politics - Mr Trump necessarily has to take him on with the same blowhard red-faced rantathon that he's indulged himself in so far - shouting at China, for instance, over the seizure of a not-particularly-significant US naval probe. So the bromance will fade rather quickly. The White House's new inhabitant knows, for one thing, that he has to keep the rage up. That's how he continues to signal to his core electorate that he's battling for them. That they're not small. That the type of language that they recognise and admire is being sent out to do their work in the world. That 'the system' is still being attacked - in whatever new way lies to hand. That America's status, and by extension the status of everyone in America who feels threatened by globalisation and interdependence, is being puffed up by talking about the great big stick they've got ready if they're really forced to use it.

The second reason why an era of eyeballing is likely is that Mr Trump no doubt recognises his mirror image when he sees it. Where have we seen this before, this concentration of power in the hands of one bully-boy leader prepared to talk over the heads of 'the political classes'? This interest in personal and familial enrichment, this decadent life of gold elevators and big plush hotels? This constant demonisation of the many apparently sinister non-national and non-nationalist forces of opposition who threaten 'the people', backed by the unnamed and unnatural forces of global banking and finance? That's right - in the power vacuum left by the collapse of the Soviet Union, among the ruins of which a lot of extremely unscrupulous people became very, very rich. Richard Nixon was paranoid without much cause. Mr Trump can see a very good reason to be paranoid in the reflection cast back at him by Mr Putin and his increasingly-impressive cast of mini-mes and yes-men across both Europe and the world. 'What would I do in his position?', Mr Trump will ask himself. That's right: threaten, negotiate in bad faith, and then throw any agreement in the bin as soon as its usefulness has expired.

That'll tip everything into a new cold war defined not by staring at each other in Berlin, but by shouting at each other over the internet. Because what will inevitably happen if you pitch a comedy wrestling fanatic with a serious inferiority complex up against a top-off, horse-riding, judo-loving, bear-wresting ex-KGB tough guy? Probably this: a jaw-jutting, musk-spewing, arm-wrestling struggle. That's the third reason we're heading for confrontation between East and West, whatever the warm words that you'll hear for now: the sheer machismo of the new world disorder, not so much a howl of rage against modernity as a grunt of image-building weightlifting effort for the watching masses. It's not going to be pretty - like watching not one but two past-their-best John Waynes strutting around the international system as if they own the place. The fact that, yes, they do actually own the landscape makes things even worse.

International diplomacy has always been a grey world. Real people have always got crushed beneath its wheels. But the next four (and quite possibly the next eight) years are going to be marked by a kind of hyper-'realism' that is no realism at all given how much a transactional politics this stark raises the risk of outright confrontation. Consider these questions: will an apparent pass to do what they like in Syria mean that the Russians will cut their Iranian allies loose, allowing harsher American economic or even military action against Tehran? Will any American soft-pedaling on the defence of Eastern Europe get the Americans the reward of a harsher Russian line on China in the Pacific? Will the two powers want to team up and stifle internet neutrality and free speech itself? Will Washington's sudden silence on human rights and anti-Russian sanctions win them some juicy Eurasian business contracts? Those are deals for high stakes indeed, and they could easily come apart at any time. If they were ever going to work, they would involve both men learning to walk a diplomatic tightrope. Any such agreements would also depend on the two Presidents understanding the role of empathy and trust, lest immediate defection from any one of those deals become too tempting. Their past actions demonstrate no aptitude for this whatsoever. Betrayal, mistrust and the increasingly-fervid swamp politics of national self-interest are far more likely.

So - welcome to the age of the gangsters. It's going to be yuge. And yugely dangerous.

Monday, 12 December 2016

Beyond the polls - Labour's byelection performance

So now, as we get close to the year's end, let's have one more look at the UK Labour Party's electoral performance, shall we? As you're aware, we've been tracking this in opinion polls throughout 2016, and on that measure there were some stirrings of life back in the spring, which faded over the summer and seem now to have dropped away precipitously - all fine gradations of unpopularity at a time when Labour has been lagging further behind than at any previous period it has spent in Opposition since 1945. Be that as it may, you're probably thinking 'polls, schmolls' and getting ready to say that they hardly seem all that accurate any more. There's a bit of truth to that assertion - polling is indeed getting harder - though we feel duty bound to point out that most polling still seems to be somewhere near the mark. National polling in last month's US Presidential election, for instance, was pretty much spot on, whatever the polling miss in relatively sparsely-surveyed Michigan and Wisconsin.

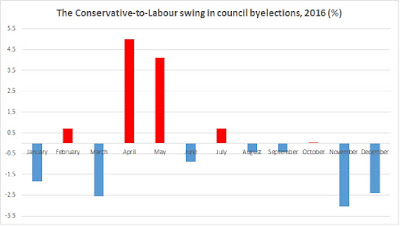

Well, there's another test for you - actual votes in actual ballot boxes, as the Liberal Democrats always used to say. And we don't just mean the May local and devolved elections, which went pretty badly for Labour everywhere outside London (and catastrophically in Scotland, where they fell to third place). There are actually local elections up and down the country almost every Thursday night, and occasionally there's an exotic Monday or Tuesday poll as well. What does the data on those reveal? Well, as you can see from the percentage numbers in Labour-versus-Conservative results (above), overall there's rather an even-steven feel to all this. If we take the 164 contests for which we can compare Labour and Conservative performance since the last Parliament - excluding, for instance, all those wards where one of those parties did not stand last time, or failed to put up a candidate on this occasion - there hasn't been a vast amount of swing in 2016. In fact, it's probably around only 0.5%, though the direction of travel is from Labour to the Conservatives - hardly an encouraging result for a party supposed to form the official Opposition, and facing an austerity government in its seventh year.

The swing towards the Conservatives has been gathering a bit of pace of late, too, as November and December appear to have been particularly bad months for Labour. That may be because there are problems with getting the party's vote out during the dark winter months. Turnout is very low, as it usually is at this time of year - particularly so in some Labour wards such as one in Lancaster covering the University, which turned in a seven per cent turnout last week. Yes, that's right, seven per cent. Overall, there was a three per cent and a 2.4% swing from Labour to the Conservatives in November and December, while those two big Labour data bars in April and May represent only a tiny number of contests - three and four, respectively. In sum, it's fair to say that on this front things have been pretty dismal for Labour, okay for the Conservatives (as they're the sitting government), but pretty good for the Liberal Democrats, who've gained a net total of 21 seats since May alone. So well done to them.

Coming back to Labour's performance, all this looks even less encouraging if we journey back to 2011 using Liberal Democrat data on contests from that year. We haven't been able to source perfect numbers on 2011, by the way, and we think that our series is a bit incomplete, so please do get in touch if you've got what you think is a complete dataset. But in any case, the orders of magnitude are clear: there was probably about a 5% swing from the Conservatives to Labour that year, over the same period in the last Parliament. That Parliament, need we remind you, ended in a very bad Labour defeat. So without looking at the opinion polls at all, we can easily see that Labour's performance is quite a lot weaker than it was in 2011, presaging perhaps a worse defeat in 2020 than the party experienced in 2015. They're doing better in London, by the way - there's a swing to Labour there of about two per cent - but given what we know about the urban nature of their remaining support and the results of the Mayoral election in London, that's not much of a surprise either.

This all fits with Labour's performance in Parliamentary by-elections held during 2016. That wasn't again too disastrous earlier in the year, with solid defences in Sheffield, Ogmore and Tooting. But recent performances have been very poor indeed, as Labour was squeezed into losing its deposit in Richmond Park and then humiliatingly pushed into fourth place in Sleaford. The first can be written off as the classic effect whereby a third party is pushed way down by tactical voting and a desire to kick the government where it hurts: the second was to be honest astonishingly bad, another indicator that Labour seems to be losing touch with whole swathes of the country. Sleaford was the strongest Conservative byelection defence since the early 1980s - more than thirty years ago.

The whole picture again looks even worse when we compare Labour's numbers to those from 2011. They had some really quite creditable performances that year, with for instance Debbie Abrahams elected in Oldham East and Saddleworth with a ten per cent increase in her party's share of the vote. Dan Jarvis won Barnsley Central with a 13.5% increase in Labour's vote there, and a 13.3% swing from the Liberal Democrats. And so on. This year? Not so hot. There was a bit of movement towards Labour in Sheffield Brightside back in May, but there was a slight swing against them in Ogmore, and the less said about Sleaford, the better. Yet again, only in London - in the Tooting contest triggered by Sadiq Khan's election as Mayor - did Labour turn in anything like the performance you might expect from the main Opposition party. If we exclude the Witney and Richmond Park byelections this year as not really comparable to the five 2011 contests, all of which saw Labour start in first place - and that's a very favourable assumption for the red side - then the same picture emerges as for local byelections. The average swing towards Labour, and away from their main rivals, in these votes was 5.3% during 2011; this year it's 2.5%. They're just not hitting even the 'heights' they reached under Ed Miliband.

Opinion polling tells us that Labour are way behind, at a time in the electoral cycle when they were a little bit ahead in late 2011. That's bad enough. But you don't need to listen to pollsters. The local contests held every Thursday night tell us the same thing, if perhaps in less stark terms. Parliamentary byelections confirm the picture. The difference between 2011 and 2016 doesn't look as bad when you look at these real votes as it does when you look at the polls, but there might be good reasons for that. For one thing, we've been looking here over a whole year - including a period in the spring when Labour's polling didn't look quite so miserable as it did both before and after that brief (and very limited) recovery. And for another, the government of the whole UK is not on the line in these local contests. The story from the ballot box looks, at the very least, compatible with the pollsters' numbers.

You don't require opinion polls to tell you that Labour's popularity in this Parliament stands some way below its scores during the last. The question then becomes: is anyone listening?

Monday, 5 December 2016

Richmond Park: Liberal Democrat fightback?

So: what does the Richmond Park byelection mean? How best to place it in context, speculate about its likely effects? The first and most important thing to say is: it means absolutely nothing. Voters love a chance to aim a kick at governments they have absolutely no intention of supplanting. The ex-Conservative MP who lost his seat, Zac Goldsmith, has failed to cover himself in glory over the last year, and was an easy target for some pretty angry fairly small 'l'-liberal and pro-EU voters disappointed when Mr Goldsmith appeared to go all-out to trash his previously-independent image.

The history books are also full of Liberal Democrat byelection gains, sometimes on huge swings, that went back to their previous allegiance come the subsequent General Election (think Christchurch in 1993 and 1997). Last and by no means least, if you take a look at successful Liberal Democrat gains from the Conservatives since their historic triumph at Orpington in 1962 (above), you will see that the result in Richmond Park is perfectly normal and indeed average for this sort of thing. There are eleven Liberal Democrat gains on a swing smaller than this one, and nine larger. Small byelection gain: no-one hurt (except Mr Goldsmith).

Even so, and as usual on this blog, we think it likely that are some lessons to be teased out here. The first thing to say is that the Liberal Democrats are likely to get something of a polling boost from Richmond Park. Third parties - indeed, at the moment fourth parties in the Commons - desperately need attention. They need publicity, that oxygen of political life, to get onto the public's radar. Well, they managed that this week, just as the new Social Democratic Party secured vital wins in 1981 at Crosby and in 1982 at Glasgow Hillhead. Without byelections, the SDP might never have achieved the political afterburners and the stratospheric poll ratings that they did manage: the Liberal Democrats have to hope for the same effect now.

Our analysis of polling boosts following such byelections - Liberal, SDP and Liberal Democrat gains from the Conservatives - should offer the party a little bit of hope. Since 1962, the average boost in the polls provided by these wins has been 3.2 points one month afterwards, 2.3 two months afterwards, and 1.9 three months later. Given that the Liberal Democrats are currently languishing at about eight per cent in the national polls, that might see them break into double figures and rival the United Kingdom Independence Party for third place in the polls: not much, perhaps, but something. The effect will fade a little as the New Year goes on, but the added attention - and the boost to confidence - gained in Richmond Park is probably worth having.

The more important point to note here is that this result might give the Liberal Democrats a little bit of a guidebook on where to focus their very limited resources. Richmond Park is one of the most affluent seats in the country, full of established richer families and young professionals. It is also very, very pro-European, and was the twenty-eighth most Remain constituency in the country at this year's European Union referendum. Only 28% of inhabitants voted Leave (you can download all the data here). So here's the thing: the Liberal Democrats now know that they can get some sort of purchase back in the political arena if they focus on wealthier, pro-European areas with Conservative MPs.

It's important to stress that public opinion on this question doesn't seem to have moved much since the referendum, though there have been a couple of polls putting Remain ahead again. And voters hardly gave Sarah Olney, Richmond Park's new MP, a ringing pro-European endorsement given the fact that everyone's vote fell. Remain voters were probably just that bit more motivated to turn out (on a very cold day) and give the Government a bloody nose. But that's the point: differential turnout is as good as anything else in winning seats, and the Liberal Democrats can also squeeze the Labour vote (as they did in Richmond Park), then so much the better.

There are probably only a few seats where all this holds. We've taken a look at the top forty Liberal Democrat targets currently held by the Conservatives and 'scored' them in a very crude manner - just adding together the (percentage) Conservative majority and the Leave vote back in June. We do know that this risks adding apples up with pears, with two scores reported along very different ranges, but bear with us. The lower the score, the more vulnerable these seats are to the pro-European Liberal Democrats if this issue continues to dominate British politics (it probably will, by the way).

The results? Well, if we were making Liberal Democrat strategy, our top targets would be the following nine seats: Twickenham; Bath; Kingston and Surbiton; Lewes; Cheadle; Oxford West; Cheltenham; Thornbury and Yate; and Sutton and Cheam. The two Conservative MPs in these seats who voted Leave might be well advised to start mending fences with some of their Remainer constituents, or they might be looking for a job after the next election. So Maria Caulfield in Lewes and Paul Scully in Sutton and Cheam better not get all that comfortable in their House of Commons offices just yet. Some Conservative Leave MPs in the next five seats on this measure - Derek Thomas in St Ives, Will Quince in Colchester, and maybe Christopher Davies in Brecon and Radnor - should also probably feel quite a bit less secure in their jobs this week.

There's a wider point here, as well. The Liberal Democrats now have a chance to get into full cry about an issue they feel passionately about. They get to pass the authenticity test. They must now shout, over and over and over again, about how pro-European they are. It doesn't matter how sick they get of it. Remember 'tough on crime and tough on the causes of crime'? You have to repeat a sound bite every day for years if you want it to gain traction, especially if you're as small and as starved of media attention as the yellow team now are. Because they have a precious opportunity to corral the 22% or so of voters who actively want a new referendum - Britons who are very, very upset about the result of the EU referendum, and who would like to reverse it if they could. Public opinion may not have changed much, but it is pretty divided. 21% of the voters are more than happy to keep free movement if that's the price of free trade with the EU; 28% would 'probably' go along with it. That's half the country open to a very soft Brexit indeed - many, many more people than currently say they will vote for Tim Farron's party.

Is this defying democracy? Not really. Leave campaigners wouldn't have given up if they'd lost the referendum. Parties don't just disband themselves if they lose a General Election. And most importantly, that sort of theoretical question doesn't matter. The Liberal Democrats now have a cause. They have cut-through, even among tepid Remain voters and agnostic Leave supporters who will see a party that at least believes what it says - and says it clearly. Labour is tragically divided, and in a terrible dilemma, over Brexit - torn between Leave-leaning northern towns and Remain-focused southern cities: its response to this crisis has been tepid at best, and incoherent at worst. Polls now show that the Liberal Democrats could even rival or overtake Labour if they are the party of 'Remain', and Labour is in favour of Brexit. Although we'd take such projections with a pinch of salt, they should clearly spy an opportunity here.

It's no surprise, from this angle, that there does seem to be some stirring in the Liberal Democrats' part of the political woods. It isn't much, yet, but it does amount to signs of life. Their national poll rating may remain in the doldrums, but where they have activists and enthusiasm, they are beginning to show up and spring back from their disastrous performance at the 2015 General Election. They have now made 21 local byelection gains since the last major round of such elections back in May: they made another on the same night as their success in Richmond Park.

It's no surprise, from this angle, that there does seem to be some stirring in the Liberal Democrats' part of the political woods. It isn't much, yet, but it does amount to signs of life. Their national poll rating may remain in the doldrums, but where they have activists and enthusiasm, they are beginning to show up and spring back from their disastrous performance at the 2015 General Election. They have now made 21 local byelection gains since the last major round of such elections back in May: they made another on the same night as their success in Richmond Park.

So the Liberal Democrats now know the ten to twenty seats where they should focus their energies. They know their issue. They have a cause. The ball is at their feet. It might only be a tennis ball, but hey, this is all looking a lot better than they could have hoped for last year. They might be able to get back to where they were before 1997, returning something up to twenty MPs. It's a start. Can they seize the moment? Well, time will tell. Time's funny like that.

Friday, 2 December 2016

Labour is moving rightwards, not leftwards

The chaos and dissent so obvious within the UK Labour Party

since its 2015 General Election defeat has helped to cover up its actual dearth

of policies. It is by no means incumbent on any Opposition to put forward a fully-worked-out roster of actual plans, especially at this

relatively early stage of a Parliamentary term. But so far little more than

‘anti-austerity’ rhetoric has emanated from the Party since its leadership

upheavals in the summers of 2015 and 2016. Even more intriguingly, what details

we are now getting suggest that Labour is merely drifting in policy terms, or

even moving rightwards since end of

Ed Miliband’s leadership. It is certainly not on the kind of left-wing

trajectory that many members and supporters perhaps imagined when they signed

up for Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership.

Labour’s sober demeanour is most obvious in the economics

field. For one thing, Labour’s current overall posture on public spending might

now be quite similar to Theresa May’s. John McDonnell (above), the Shadow Chancellor,

has since March been committed to reducing the current deficit to zero over a five-year planning horizon. But given that Chancellor Philip Hammond has just

announced that he is significantly loosening budgetary policy, and that the

Conservatives seek to reduce the overall deficit to zero only at some

unspecified point over the next Parliament, that may not in practice give

Labour much more room than Mr Hammond when it comes to spending on health,

education, welfare and the like. Here the Conservatives’ new post-Brexit

realism has closed up much of what difference there was between the parties, a

situation that could potentially get even worse for Labour. The Government’s

plans are now extremely vague, lowering the political costs of further

electorally-motivated changes in the future. If Mrs May and Mr Hammond decide

to drop even this new pledge – and the Conservatives in office have torn up all

the others – Labour could be left high and dry, committed to spending much less than the government, since they

might not then have the political capital or time to row back on their own deeply confused and conflicted promise to be quite so prudent.

It is true that Labour promise to ‘carve out’ or exclude spending on capital investment from this rule. That might allow a Labour

government a bit more leeway than the Conservatives on day-to-day spending

if Labour did exclude such outlays from fixed expenditure

limits: total government capital spending was predicted in last week's Autumn Statement to run at over £100bn in gross terms by the start of the next Parliament in 2020/21. If you leave that amount out of your balanced books entirely, you've got serious money to blow on the current side. But the amount available in practice is actually much lower. Mr Hammond has loosened budgetary policy to the extent where the net current projected surplus to help pay for all that capital investment in 2020/21 will 'only' be about £33bn. Since Labour's declared aim is balance on current spending, that's what they'd actually have to play with in year one.

It's also important that the Chancellor's new target is now a lot less ambitious than previously: he aims only to reduce the total deficit to 2% of GDP by that point. That might make available an extra £27bn over and above his existing plans, which at the moment tot up to a deficit of about 1% of GDP. That potentially reduces Mr McDonnell's generosity at the start of a Labour government to the gap between £33bn and £27bn: if the Conservatives do throw all of that war chest at winning a General Election, he'll only have a few extra billion to spend. That'll be nice to have, but it will not represent much of a shift that will be felt on the ground. It would then take some time for any difference to open up in practice rather than in theory, given both the longer post-Brexit timeframe the Government is now allowing to get to overall balance - and just how difficult and slow infrastructure spending usually proves to assemble.

It's also important that the Chancellor's new target is now a lot less ambitious than previously: he aims only to reduce the total deficit to 2% of GDP by that point. That might make available an extra £27bn over and above his existing plans, which at the moment tot up to a deficit of about 1% of GDP. That potentially reduces Mr McDonnell's generosity at the start of a Labour government to the gap between £33bn and £27bn: if the Conservatives do throw all of that war chest at winning a General Election, he'll only have a few extra billion to spend. That'll be nice to have, but it will not represent much of a shift that will be felt on the ground. It would then take some time for any difference to open up in practice rather than in theory, given both the longer post-Brexit timeframe the Government is now allowing to get to overall balance - and just how difficult and slow infrastructure spending usually proves to assemble.

Despite claims to the contrary by some Labour advisers,

Mr McDonnell’s fiscal responsibility rule is not dissimilar to the platform

Labour adopted under Mr Miliband and his Shadow Chancellor, Ed Balls. Labour do

propose some technical changes that would ease spending constraints. There will, most importantly, be a 'zero bound knockout' rule that will suspend these budgetary targets if the Bank of England thinks that monetary policy can take no more of the strain involved in stimulating demand. Increasing the expected returns to

investment might also justify more capital spending by boosting its projected returns. But the difference these changes would make to those cruelest and most

deeply-felt cuts to the current budget – for instance, to local authority

social care budgets – might prove low indeed during the first few years of any

Labour government.

One could multiply these examples in most policy fields.

The Government at the moment seems reluctant to guarantee the standing ‘triple

lock’ on pensions increases, under which the basic state pension increases by

the greater of price rises, wage increases or 2.5% every year. Mr McDonnell has

now said that Labour definitely will commit to such a policy. Given the

enormous progress made in reducing pensioner poverty over the past two decades,

and the fact that older Britons are now one of the better-off groups in the

population, using scarce resources to help richer citizens without any means

testing seems like a bizarrely retrograde version of the Labour left's supposed redistributive

politics. The same very odd logic holds

when you look at tax policy, since the Shadow Chancellor has just agreed to

back a large upwards shift in how much workers can earn before they are charged

the higher 40% rate of income tax – another regressive measure, cutting taxes for the top 15% of earners, that Labour under Mr Miliband would probably have

rejected.

Labour’s newly-regressive present stance can be seen in

its depressingly hard-line attitude to state surveillance, since the Opposition

just inexplicably waved through the new Investigatory Powers Bill – one of the

most extensive extensions of government spying powers ever seen in the developed world. It is also clear in the party’s new attitude to Brexit: Labour members

have been urged by Mr McDonnell, no doubt happy to see the repeal in Britain of

European competition laws that rule out selective industrial assistance, to

embrace what he portrays as Brexit's enormous and exciting opportunities. Labour’s

conservatism now even seems to extend to a desperate search for a new and more

conservative stance on immigration, since its spokespeople now seem to imagine

local trade union bargaining on wages and working conditions as a way of reducing Britain’s attractiveness to migrants – yet another version of Mr

Miliband’s face-both-ways emphasis on Minimum Wage enforcement and action on

people smuggling during the 2015 election.

Why has Labour seemed to become if anything more timid,

more conservative, under Mr Corbyn? There would seem to be four plausible

explanations. There is, firstly, perhaps just the desperation that comes from

looking at Labour’s dire poll ratings. They are further behind than any Labour

Opposition has ever been at this stage of a Parliament, and they are performing

much worse than they did even during the mid-1980s. May’s local and devolved

elections, and council by-elections held up and down the country every

Thursday, paint a similar – though perhaps not quite so bleak – picture. It may

be that Labour’s employment of a new polling agency, BMG, has led to a sense of

realism and pragmatism within the party’s General Election planning machinery.

It is quite likely that they are just scrambling to get back to where they were

in the last days of the Miliband interregnum.

The second potential cause of Labour’s new conservatism is

the party’s sheer want of front-bench talent. Mr McDonnell, for instance, has

little economic experience, has never been much of a diplomat, and has never

served in front-rank politics before. Sometimes that sheer lack of practise

gives him away, just as it did during the first days of his Shadow

Chancellorship – when he signed up to George Osborne’s fiscal targets before

being forced to back away from that commitment by howls of anger from within

the Labour Party. He may simply not know that his macroeconomic policy looks

rather like that adopted by Mr Miliband and Mr Balls, and is not all that immediately

different from that offered by the Conservatives. He may not grasp that

defending the pensions triple lock is basically a promise to fire off

taxpayers’ money supporting inequality.

Another reason for Labour’s rightwards drift may

originate within the Party’s ongoing – but now quieter – civil war. Mr Corbyn’s

and Mr McDonnell’s enemies, having been frustrated in their post-Brexit head-on

assault on the leadership, have now carried their resistance underground. Many

Labour MPs are simply waiting, as they see it, for the new leadership team to

implode under the weight of its lack of ability and the inevitable factionalism

that will emerge on the Labour left. There are hints, much denied, of an ‘anaconda strategy’, gradually squeezing the life out of the Corbyn experiment

by refusing to help in its painful day-to-day struggles. Within the party’s

bureaucracy, the idea seems to have taken hold that Mr Corbyn may be unsackable

– for now – but that Mr McDonnell certainly can and should be prevented from

winning the leadership after Labour's likely General Election defeat. So the Leader

and Shadow Chancellor are simply being left to get on with things, in the expectation

that they will fail to carve out any new political space at all.

Fourth and last – though perhaps most disturbingly – is

the dawning realisation among some Labour activists that this small-‘c’

conservatism is exactly what Mr Corbyn and Mr McDonnell want and represent. It is

not a bug or a glitch. It is a key part of their programme itself. As

inheritors of Tony Benn’s alternative economic strategies from the 1970s and

1980s, it might just be that this old-new Labour leadership prefers to adopt a cramped,

shuttered attitude in an age when ‘open’ and ‘closed’ are more apposite

descriptors for our politics than ‘left’ and right’. Narrow, nationalist,

illiberal and autarkic, to this way of thinking a retreat from the EU, non-Keynesian

economics that aim to change the structure

of the economy more than the level of demand, increased reliance on interventionist

policies at home, and a stronger state, are all more than congenial to a Labour

Party that is trying to slough off its European social democratic clothes

forever.

Much will depend on whether Labour’s rightwards course is

being caused by electoral tactics, incompetence, internal politicking or an

entirely new Labour ethos of nationalistic populism. The identity of the Labour

Party is involved, to be sure, but also the future of the Westminster two-party

system. The dangers Labour face cannot be overstated. Mr Corbyn and Mr

McDonnell have allowed the impression to gain a hold, for more than a year,

that they represent a decisively left-wing

alternative to Conservative rule, principled as Labour politicians have seldom

been in their opposition to austerity. Their poll ratings, and especially the numbers

reflecting which main party is most trusted on the economy, have fallen

accordingly. But now they risk giving even up their reputation even for intellectual

probity – for ‘saying what they think’.

Just as the Conservatives risk much if their new

Eurosceptical image turns out to be false or misleading, so in this way Labour

could alienate its last bastions of support: public sector workers, older

left-leaning voters now prepared to take a fresh look at Labour after what they

perceived as the ideological betrayals of the Blair years, pro-Europeans, students, cosmopolitan urbanites and younger – but economically increasingly marginalised – middle-class

professionals. British politics is in near-unprecedented flux. During this of

all times, Labour seems determined to flirt with its own extinction as a

national party of government at Westminster. Strange days indeed.

Tuesday, 22 November 2016

Labour could be staring at a historic defeat

History

matters in elections. In this year’s US Presidential contest, political science

models based on past relationships – involving, for instance, incumbent

popularity or economic growth – did better than short-term modelling based on

opinion polls. Most such models predicted a very close race, which could go

either way, and in some notable instances predicted a Trump victory. Local

election results from the 2010-15 Parliament were the clue that allowed

forecaster Matt Singh to predict that opinion polls were failing to pick up the true levels of party support running up to the UK’s 2015 General Election.

So if we

want to look ahead to the next General Election, and for all opinion polling’s

recent problems, it is probably still useful to look at where we are now in UK

polling. It should be quite a simple job to look at present levels of support

for Labour in Opposition, and the Conservatives in government, and to project

what will happen next based on past experience.

We've done this before, of course, and this is but the latest installment of a long-running series tracking Labour's chances, on the lines of historic trendlines, all the way to the next election - whenever it comes. We've had a go at these sums on three separate occasions - last November, then again in January, and for a third time in April. It's fair to say that none of it was particularly good news for Labour. In November we thought that they would win between 26% and 29% at the next election. In January those figures stood at 25% to 28%. In April, the average had improved a little - to 27% - but that pitiful number wasn't much to set Labour hearts aflame with hope. Perhaps nothing can, these days.

So - let's go again, to test how the main Opposition party's poll ratings are tracking past performance. Let’s

start with the deficit between Labour’s numbers and those of the Conservatives.

Right now, if we take each pollster in the field’s last results at an average,

Labour is a long, long way behind – thirteen per cent or so. They have never before

been so far behind while in Opposition at this stage of a Parliament, about nineteenth

months following the previous General Election. The nearest they have come is

the eight points by which Neil Kinnock’s Labour lagged the triumphant

Thatcherite Conservative Party in December 1988. Oppositions have more often

actually led the Government in the polls at this point: even in 1980, with Labour

deeply divided, Michael Foot in his very early days as leader was able to enjoy

an eleven-point lead over a very unpopular government struggling with high

inflation and unemployment.

An even

worse picture emerges when we look at what might happen between now and the

next election. At no time in the modern era, if we take that as meaning the

period since 1970, has Labour in Opposition gone up in the polls from this

point (see above). They basically stood still between 1993 and 1997, as a youthful and

popular Tony Blair managed to keep their ratings very high all the way through to

an election: between October 1993 and May 1997 Labour’s polling score fell only

by 0.4%. But they have more usually fallen quite a long way. The unwanted

record for such a decline is held by Michael Foot’s Labour between 1980 and

1983 as the party split and threatened to break up altogether. In less than

three years, Labour’s polling score fell by a huge 19.6%. In fact, the party

has on average while in Opposition lost 7.2% from this point in the Parliament.

Since the party now stands at 29%, that would imply a score of 21.8% at the

next election.

It is

possible to put a rather more positive gloss on these apocalyptic numbers.

Labour at each General Election has been historically overestimated by polls –

by perhaps 1.5%, or a little more. If pollsters’ new post-2015 methods have

eliminated this polling error (a very generous assumption, but one which might prove

sustainable), then 1.5% or even more of the expected polling ‘fall’ from this

point to the next election has already been eliminated as an artefact of the

polls alone. So given the extent of pollsters’ post-2015 reassessments Labour might

actually hope to receive 23.3%, or even slightly more. Let’s avoid the perils

of false specificity on as generous a basis as we can muster, and round this

number up to 24%.

Realise this: Labour's rating is therefore failing to track even their pathetic polling performance over the winter, when on this exact basis the party might aspire - at best - to touch between 26.5% and 27.5%. Its numbers are still sagging, still dropping away from historic norms. It's like a slow puncture rather than a blow-out.

What,

though, of the Conservative Government’s likely score? Well, at the moment they

stand on average at 42%. The honeymoon effect of a new Prime Minister is

probably still affecting this rating, although we should also bear in mind that

the Conservatives still probably have a lot of scope to soak up UKIP voters if

that party does implode in the way that certainly seems possible. In any case,

the evidence since 1970 is that the Conservatives’ vote share at the next General

Election might be a little higher than

it is polling at the moment – by an average of 1.8% or so. Let’s again not be too

precise, and call the gain 2%. That would see Theresa May’s party attracting 44%

at the polls

The last

stage of this analysis is to look at how these very rough figures might

translate to numbers in the House of Commons. A result which saw Labour gain 24%,

and the Conservatives 44%, would mean on old boundaries a Conservative overall

majority of around 150, with Labour down on about 160 seats. On the new

boundaries likely to come into force late in 2018, these shares of the popular

vote would again give the Conservatives an absolute majority of perhaps 150 in

a smaller 600-seat Commons, with only something like 150 Labour MPs returned.

That would be the party’s worse showing since 1931.

If

Labour do indeed receive a score down in the lower- to mid-20s, and the

Conservatives something over 40%, the next General Election will see Labour

very badly, indeed historically, savaged: it is possible that the party will

suffer a ringing, enduring defeat that will be hard to recover from in any near

or foreseeable future. It should be stressed that this is a very crude way of

looking at these numbers. Labour will probably do better in urban seats, and particularly in London, than this raw data suggests. And in these surprising political

times, during which so little seems solid, Labour might somehow be able to

escape the fate that its previous experiences suggest is likely. But right now,

the historical auguries are very, very ominous indeed.

Note: an earlier version of this blog first appeared on The New Statesman Staggers Blog on Monday 21 November, under the title 'This is the Moment When Labour's Polling Gets a Lot, Lot Worse'.

Tuesday, 15 November 2016

Stop saying that Trumpism is about economics

The election of Donald Trump to serve as President of the United States (above) came as a shock to many people (though not, of course, if you've been refreshing this page). The reaction to that shock in Europe, including the UK, has been some pretty justified concern, and even fear, as to what President-Elect Trump will do with all that power. Will he undermine NATO, plunge us into trade wars with China, and use his bully pulpit to poison race relations across the Western world? Or will things turn out a bit calmer than it seems right now? Possibly a bit of both, though as you'd imagine we tend towards the former interpretation.

In any case, the next and inevitable line of the reaction was the immediate analysis - that natural and understandable stage of contemporary history which sees people asking 'how on Earth did that just happen?' On the Left, one big answer became: this is a judgement on globalisation, on elite economics, on rising inequality, and on the disappearance of good, highly-prized blue collar jobs. Given that Hillary Clinton lost this election in just three rustbelt states plagued with manufacturing decline - Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin - there is prima facie some evidence for this. Mr Trump's constant inveighing against trade deals that have 'cost America jobs' (they probably haven't), as well as the thinly-veiled antisemitism of his attacks on 'global elites', will undoubtedly have gained him votes here. There was a swing towards the Republicans, and away from the Democrats, among lower-income voters. There's something there. It's important.

This is not, however, the whole story - or even, in our view, the main part of it. Elections are above all complex things - a meeting-place and a storehouse of narratives, interests, loyalties, identities and clashing conceptions of individual and state that cannot possibly be contained in a vessel marked 'economic decline' or 'economic anxiety'. And so it was with this election - one fought as much between the urban and the rural, and coalitions of imagined 'future' and 'past', ascendance and restoration, as it was between the economics of success and failure.

First things first: say what you like about all this, but Hillary won the popular vote. Following on from an administration which helped to create jobs at a not-inconsiderable pace - and had just got to the stage of raising wages from their pre-crisis baseline. Secretary Clinton is probably going to win the whole thing by two percentage points, or even more. Having already run past Mitt Romney's vote total, she's surging on to rack up the highest number of actual votes anyone not named 'Barack Obama' has ever won. Not much of an economic revolt there, at least overall, and especially in states where people of colour - the group by far worst hit by the Great Recession - live in great numbers. Secretary Clinton made Georgia and Arizona quite competitive, those states taking their next steps towards the Democrats' blue column, and even pushed forward quite a long way in deeply-red Texas. Where is our economic analysis when it cannot make sense of the fact that admittedly-suspect opinion polling tells us that Hillary won voters asked specifically about the economy, when she still captured the majority of the most disadvantaged Americans, when those hurt most grievously by inequality mostly voted for her in the same proportion as they did for President Obama? Yes, it does seem as if African-American and Hispanic turnout did fall, but here again there's but little analysis - for instance in vital North Carolina and Wisconsin - of the role that new Republican-inspired voter identification laws played in that process.

Next: there is an absolute stack of social science evidence that shows that the propensity to vote for the new wave of Right-populism is correlated, not so much to income and economic class, but to the extent to which voters hold authoritarian views themselves, and to feelings of cultural isolation among older, whiter, less educated male voters. It's as simple as that. Reacting to a feeling of cultural threat, surrounded on all sides by what appears to be a whirlwind of change, many older white men - in Britain as well as in the US - will seize on conjoined visions of the nostalgic and the radical. Nostalgic, because the noise given off about race, sexuality, gender and crime take them back to an imagined and settled past; radical, because they feel in their hearts that, so vast are the upheavals, huge steps will be needed to get there. We've got data coming out of our ears about a declining sense of white privilege and white authority, hostility to immigration, dislike of multiculturalism, and the backlash that this election - in part, and only in part - represents. Apparently it's all about jobs, though.

Thirdly: economic analyses of elections in the United States seem to give nothing but a passing nod to the peculiarities of American culture. Only rarely do we get a bottom-up analysis of events seen from the grassroots, witnessed from that semi-fictitious Main Street of Middle America that is such a powerful draw precisely because it almost always exists only in idealised (or, sometimes, dystopian) fiction. Where are our European annalists who've been in and out of the bars and backstreets of North Carolina, Ohio and Iowa - all states carried by President Obama, but lost by Secretary Clinton? Where are the writers who understand the appeal of the American Hero, alone, unsupported by class and party, riding out of the sunrise to save the day - assuredly one more element in the rise of Mr Trump, an independent insurgent who has seized control of a whole party? Where is the understanding about exactly why the Big Beneficent Plutocrat might be preferred to the Narrow, Mean Professional? You'd think that all those years of cultural studies and the linguistic turn would have engendered at least some awareness of the American mythos. Mrs Clinton failed to evoke hope, change, a better future - those key elements of that cliched, but imaginatively very real, American Dream that President Obama understood so well, but could not in the end use to help his party. She failed to outline, clearly enough, what her America would be like. She wasn't crystal clear, with just a few key lines. So she lost. Supposedly everything is about manufacturing, though.

Further: wealthier Americans continued their adherence to the Republican Party, despite a bit of weakening here and there where suburbanites and highly-educated citizens decided that they just could not face voting for a candidate as grotesque and unqualified as Mr Trump. Party trumps everything else, apparently - especially with at least one, and perhaps one or two other, seats on the Supreme Court at stake. It is worth exploring the other side of an economic case that does have a little merit: an upper-middle class and a wealthy, older citizenry that is so sated by superabundance, so secure, crudely in fact so rich and so ripe for autocracy, that they think that the Republic will always stand, that capitalism will always serve their interests, that chaos can't ever come to their door. Well, if this experiment in demagoguery goes wrong, they are about to find out just how wrong they are, aren't they?

Fifth: has everyone forgotten the culture wars? Mr Trump makes great play of being a values-neutral and ideologically-light businessman, up for any deal, so long as it works - a good display of a very cynical and regressive ideology in itself, in fact, though we'll let that pass for now. But the election just past was in fact the culture wars election par excellence, pitting a woman against a man, the coasts against the interior, the rust belt against the sunbelt, old industries versus new industries, the universities against the workers, the country against the city. This, for one thing, fired up hidden sexism everywhere - which that inconvenient thing, actual evidence, shows can be even more successful in that high-energy, high-emotion setting Mr Trump and his team deliberately engendered. More quantifiably, a huge category of 'missing whites', who gave 2008 and 2012 a miss both because President Obama was so impressive, and in the former case because his election seemed so likely, showed up in the Upper Midwest - just as they had in the 2014 mid-terms, the last time we saw a US polling miss on this scale. Much more research is required here. Are these older, less educated, less regular voters really likely to be those angry factory workers so exercised that their jobs have, or might be about, to move to Mexico? Or are they likely to be fired up by what they often say they are - Washington 'corruption' and gridlock, the right to bear arms, abortion, resentment at the cultural cringe they feel forced to wear? We'll take a wager on the latter, thank you very much.

Sixth and last: what about the campaign? To shove everything into the file marked 'economics' leaves out almost everything we know about recent contests, in which many more votes are decided late on, and in which very busy low-information voters have to make decisions in a fog of fake news and from within social media filter bubbles that are draining the very heart out of our democracies. In case you hadn't noticed, one widely-spread set of stories on Facebook were the stolen Wikileaks emails out of the Clinton campaign, which although they were for the most part stultifyingly boring, helped to paint Secretary Clinton as a consummate and scheming 'insider' - that worst of all insults if you're looking at this from (for instance) the Florida Panhandle and you feel Washington has forgotten all about your views and your morals.

Then, to cap it all off, the FBI said that they were looking into Clinton's own emails - opening up all the old wounds about corruption, cover-ups, evasion and possible criminality which have dogged both Clintons since the early 1990s. It was just too much to shrug off when Mr Trump was already well within striking distance. Although all the evidence is not in (and might never be in), it probably dragged her down just a tiny bit at the end. If we were writing the history right now? The razor-thin margin of Mr Trump's victory in the key three states would be more than explained by Director Comey's letter. And if Hillary had narrowly pulled through, with just fifty or sixty thousand votes swinging it the other way, everyone would be saying 'oh, it was the demographics, it was rising wages, it was the jobs miracle of the Obama years that won it'. The narrative can be spun on a sixpence. Don't let anyone do that. The Russian government that helps to sponsor Wikileaks, and the FBI that blew up a big story about what it then admitted was nothing, played a key role here. Focus on the economics? You miss the whole trick.

So here's what the economic interpretation misses: the economics of success as well as failure; the psychological and emotional drivers of Right-populism; the whole context of American history and culture; the actual structure of the Republican vote; culture and gender's role in the whole debacle; and campaigning politics themselves. So pretty much everything, really.

What is most galling about all this is that the crude economic interpretation that UK Labour and some of its allies appear to be indulging in takes away the electorate's dignity of choice - the voters' autonomy, self-possession, individual definition, personal beliefs. Yet again, this is the Left saying: 'you must have been desperate to do that'. 'You must be raging against something'. 'You must be victims'. 'What were you thinking?', they say, in the same slick metropolitan tones that lost them all those votes in the first place - leaving an implicit sneer and disqualification in the air that will do just as much to normalise and validate Mr Trump as will all those conservatives who choose to serve in his administration. Highly-educated Left-leaning politicians and activists, who for many years have increasingly possessed degrees and lived in cities, don't get illiberalism. They never will. So they say it has to be all about fear, loss and self-interest. Perhaps it's not. Perhaps it's because you don't talk like anyone who most people have ever heard in person. Ever considered that?

So there you have it. It is abundantly evident that the European Left cannot cope with complexity, nuance, change, uncertainty. It is even clearer that it is being consumed by a peculiar type of cod-political and sub-Marxist economic determinism that most good A-Level students would rule out of their essays on the 1848 or 1917 Revolutions. It's so cramped, the 'white economic anxiety' headline. So limited. So impoverished. The Left won't listen, and they can't hear, and they fail to see. And then they lose: over, and over, and over again.

Monday, 7 November 2016

Can Labour pull together?

The UK Labour Party's current trials and tribulations have at their heart - indeed, perhaps may always have had at their core - a tension between 'utopian' and 'authoritarian' politics - between the world that might ideally be, and the messy process of forcing our way there. These do seem to now lie at the heart of the new Labour project. For those two elements in Jeremy Corbyn's appeal as Labour leader (above) have up until now been yoked together in a potent mix. There are signs that the abatement – for the present – of loud internal dissent will allow them to come into the open.

Corbynism undoubtedly appeals to newer Labour members and supporters, many of them older returnees who had become disillusioned during the Blair and Brown years which they perceived to be full of fatal compromises with a conservative (and Conservative) ‘establishment’. Its public agenda is at least a clear one, and has many points of contact with Soft Left Milibandism or even the social democracy of Labour’s centre. No foreign wars in co-operation with American power, or at least not without explicit United Nations agreement and a wide basis of international support; the reversal of public sector austerity; a stronger government, with higher tax rates on business, executing more active industrial and budgetary strategies that also rely on higher borrowing – and a reshaping of the economy, rather than just fighting the ‘symptoms’ of poverty tackled by tax credits and higher welfare spending.

This strategy - let's term it relatively 'utopian' - has two huge advantages over the apparently uncertain and exhausted centrist strategy pursued during the New Labour years between 1994 and 2010. The first is that it incorporates the outburst of Left populism so obvious elsewhere across Europe within the Labour Party, rather than leading to a rival party setting up on Labour’s left – the role the Green Party seemed to be playing in the run-up to the 2015 General Election. The evidence from local by-elections this year is clear: where there are Green votes in urban areas to pick up, Labour is now well-situated to draw on them as a new reservoir of support. The second point is that the strategy has led to a much, much larger party, now numbering around 600,000 members – about triple the number it was able to mobilise before the 2015 General Election. There seems little doubt that such resources of human ambition and hope might prove a formidable weapon in any political attacks on the sitting government. Labour has, indeed, already tried out such campaigning methods – holding a ‘national day of action’ in September against Theresa May’s grammar school proposals.

Yet at the same time many of the other elements in the Corbyn project militate against the more kaleidoscopic, community-orientated and populist elements in this programme. Here is where the ‘authoritarian’ elements of the analysis come in. Most of Corbyn’s popularity comes from the sense that he backs the new and pluralist Left that has emerged across the country to protest against austerity. But the politics of the 1970s, from which Mr Corbyn finds it hard to escape, are much more centralising and controlling than at first appears.

The leader’s office apparently shows little interest in a united ‘progressive alliance’ with the Greens, Plaid Cymru and the SNP – a matter of faith among many of Corbyn’s younger and more idealistic followers. A number of his own supporters wrote an open letter to the Labour leader protesting against his recent appearance on a Stand Up to Racism platform with members of the Socialist Workers’ Party, a far-left grouping with a troubled history that has made it anathema across most of the British Left. The campaigning group Momentum, so vital when installing and defending Mr Corbyn's leadership over the last two years, looks to be struggling to solve the contradictions between members stressing either its representative or its participatory nature. Just as seriously, Corbyn’s personal defects as a leader – and especially his controversial past, as well as his own style and image – are clearly giving elements of his hard core support pause for thought. Paul Mason, the campaigning journalist, was taped accepting just this case in a recording leaked to The Sun newspaper.

The contrast between words and deeds can again be seen in Corbyn’s attempts to bend Labour’s National Executive Committee and Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) to his own demands. Given the struggle for power within Labour, such an effort is perhaps understandable, even unavoidable; but he risks replacing representative democracy, across the NEC and PLP, with a type of plebiscitary democracy based on his ‘mandate’ from members that such structures are deliberately designed to mitigate and dilute. It is no accident in this respect that the first serious signs of dissent about his leadership are being seen in the trade union movement, deeply worried about its own voting rights and voice within the wider Labour family. This is one reason why renewing Trident looks set to remain party policy, even while Mr Corbyn’s erstwhile supporters in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament complain as loudly as they can about this u-turn.

For now, at least, these tensions can be managed. But they are unlikely to go away. All the evidence we have from local elections, by-elections and polling points to the fact that Labour face a terrible defeat at the next General Election. When real wages are likely to decline following sterling’s steep depreciation, and the Government is likely to tie itself in knots over Brexit, this is a missed opportunity of enormous proportions. At the same time, boundary reforms are likely to throw up a small but significant number of chances for local activists to prevent the re-election of Labour MPs who have vocally opposed their leader. The bitterness these local fights will evoke might be difficult to contain, and some Labour MPs may decide they have nothing to lose by sitting as independents or fighting by-elections in the last two years of this Parliament. A formal split seems highly unlikely, given the MPs’ cultural loyalty to Labour as well as the electoral catastrophe that would probably befall both halves of the party after any split. But a prolonged cold war between MPs and leadership, which in the end leads to splintering and incoherence rather than split, is quite likely, and perhaps even probable.

In this situation, the non-Corbynite parts of the Labour Party must deeply rethink their strategy. They have a huge opportunity to reach out to their own party’s Left as it becomes increasingly disillusioned with Corbyn over the next year or two. They have hitherto developed the tactic of speaking out when they want, on the subjects they want – all the better to at least affect public policy in some ways while the leadership team fumbles. Now they might draw these threads together, to show what a new agenda would look like if it was to appeal to the whole non-Corbynite party, from Soft Left to Old Right and through to the social democrats of the ex-Blairite centre.

Their list of priorities might include, though not be limited to: massive, cascading devolution throughout England, as well as to Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland; the development of new sectors of the economy through regional and local co-operatives and ‘New Deals’ fostered by rolling programmes of inclusive devolution; and productivity-raising projects in both physical and human capital that long-term borrowing by cities and the UK’s devolved administrations might unlock.

Now the labels ‘Blairite’ and ‘Brownite’ are obsolete, Labour’s non-Corbynite MPs – and members – have a duty at least to try to make such an agenda work. It might be that Labour is now too far gone for all this: that globalisation, the changing economy and the political strains of large-scale immigration have smashed for the foreseeable future the alliance of metropolitan liberals and blue-collar workers that any social democratic party must assume. But political parties can come back from the wilderness very quickly, as the majority seized by the Canadian Liberals last year demonstrates. The years immediately ahead look very bleak for Labour right now, but if the more pluralist strands among its new support can somehow make common cause with its long-standing activist base, there might at least be hope of mitigating the long-term damage.

Note: a previous version of this blog first appeared as part of the Sheffield Political Economy Research Group's website on 3 November.

Monday, 31 October 2016

British lessons for the American election?

Many British observers looking on at the US Presidential election have started to feel hairs standing up on their necks. A front-runner most people think is now the inevitable winner? An establishment choice that it seems inconceivable won't make it over the line somehow? Polling that mostly points in one direction, but which seems more divided and confused than ever before? No-one who's had to suffer both through the 2015 UK General Election, which so many people thought would bring Labour leader Ed Miliband to power, and the 2016 European referendum, which most voters thought 'Remain' would win, can fail to see the parallels with Britain's recent travails. Liberals, progressives, radicals, internationalists: they all thought that they were at or over the line. They discovered that the country they lived in wasn't quite what they thought it was. Might the same thing happen now, with Hillary Clinton (above) the victim of a similar polling failure?

The parallels actually don't fit very well. There are four reasons why, and each of them is important in giving greater statistical clarity to the present US election, as well as thinking about the British contests just gone. Let's have a look at them, in no particular order:

1. The British polls weren't actually all that wrong.

Remember that the 2015 General Election looked very tight, giving off a nip-and-tuck, neck-and-neck quality all the way through... If you trusted the polls. That meant that a far-from-massive miss turned a projected Hung Parliament in which Labour might have sought to form a government into a small Conservative majority - a polling miss of about 6.5% if we add up the inaccuracy on the Labour and Conservative scores. Polls got slightly closer in the EU referendum, with statistical averages on the eve of the results registering an exactly-equal deadlock to a Remain lead of four points (Leave, of course, won by 3.8%). In fact, if we just average the last poll from each company in the field, we get a Remain lead of 2.5% - and a total polling error, from polling lead to final numbers, of 6.3%. Note here, though, that UK election polls don't actually have that fantastic a record when compared to their US cousins. British polls usually overstated the government by a long way in the 1980s, and then again under New Labour: there was a five-point overall miss in 2001, for instance. The Americans, as we shall see in a moment, have always done rather better. And they haven't been disgraced in any of the last few contests - even very tight ones such as 2000 and 2004. So we can't even be that confident that our actually rather narrow range of error can be read across to the new contest on the other side of the Atlantic.

Then there are differences in the detail. The Brexit vote continuously threw up a so-called 'mode effect': online polls seemed to show Leave narrowly ahead, while some phone pollsters showed a large Remain lead. There's not such a large difference in the current Presidential election: YouGov's online panel, indeed, is returning a fairly constant four-point lead for the Democrats' candidate, which is right in the average range that we'd expect from all polling. The two cases are very dissimilar, and even a May 2015-style error in the US might not allow Mr Trump to prevail. US pollsters are savvy, experienced and multifarious. At the time of writing, Mrs Clinton leads on average by between three and seven per cent. It will be a large and unusual polling miss - even by British standards - to overwhelm that lead. But beware: that's exactly what we got in 2015 and 2016. And the British polls had been getting more accurate, in 2005 and 2010 not ending up all that far off if we look at the overall average. Then look what happened. The miss can come out of the blue. It could be there, but it will have to be pretty big.

2. The USA just has a lot more, and more accurate, polling.

It's true that British General Elections bring in a lot of numbers. But American elections throw up a lot more information - many thousands of polls at state as well as national level which just about confirm the national picture we've got of a not-particularly-large, but for now stable, Clinton lead. And it's usually right. Take figures from the venerable Gallup Organisation, which has now stopped horse-race polling after a chastening polling miss in 2012 (the two-party result was a total of five points different from their final poll). If we look back to 1980, their final numbers were never more than 6.8% away from the actual outcome - and were as near as 0.2% in 1984. Polling averages since 1968 have usually predicted the final scores within a range from exact accuracy to a four point miss. In 2012 the polls were on average 3.2% away from the actual election numbers.

We also cannot emphasise enough the sheer amount of lower-level polling conducted among the individual states that make up the US. Yes, polling of individual Westminster seats got a terrible reputation because of their apparent 'miss' in 2015 - but bear in mind that this was an unusual experiment, funded by the Conservative peer and philanthropist Lord Ashcroft, and which usually made its most egregious misses highlighting the wrong question in Liberal Democrat seats - namely, 'would you vote for your local MP', rather than 'would you vote Liberal Democrat'? More general regional polls, for instance of the Liberal Democrats' apparent stronghold in the South-West of England, got things spot on. State polls in the US, on the other hand, are telling us a story that is intuitively understandable: Donald Trump is doing better than Mitt Romney among blue-collar white voters in the Upper Midwest, while Secretary Clinton is doing better than President Obama in the South with Latino voters and college-educated whites who detest Mr Trump's plunge into Know Nothing politics. That doesn't mean the picture's right. But it is an important confirmation of the national numbers from experienced pollsters who've mostly done all this before. We didn't see much of that in Britain.

3. Drawing in new voters probably won't help Donald Trump.

It's actually a mistake - one which we shared at the time - to think that the British polling misses are to do with 'shy' anyone. In 2015, there was a large framing error which brought too many politically-aware young people into the numbers; in 2016, there was a large turnout of unlikely and unusual voters who thought that at last someone might listen to them about immigration, border control and national sovereignty. So Republicans hoping for a 'shy Trump' effect, under which Americans too embarrassed to tell anyone they are voting Trump nonetheless pull the lever for him in the secrecy of the polling booth, might be waiting a long time for their surprise. Mr Trump didn't manage this in the primary season: indeed, his voters were actually a bit better off than the other Republican candidates' were. He actually underperformed his polls (on average). And there's no evidence at all that he's pulling in new voters or new registrations. Indeed, British readers should in this respect remember that, as we draw more people into the American electorate, it's likely to become more Democratic as poorer voters get pulled into the sample. There's not all that much data to say that such people are more likely to favour Donald Trump.

4. The early vote doesn't look the same.

It's illegal to snoop around the early postal voting in Britain, and it's still more frowned on to report its content. But there's not much that the election authorities can do - beyond threatening prosecution - to stop albeit-vague news of how it's going leaking out. In 2015, Labour officials knew pretty early on that the swing that they needed wasn't happening. In 2016, Labour MPs in particular - and especially those with seats in the North of England - thought that the contest was over pretty much before it began, as they picked up talk of a huge Leave vote from their constituents that even a last-minute switch back to Remain couldn't make up for. Things in the US right now don't sound anything like that, and in fact those who know think that on balance things look pretty good for Mrs Clinton. They look particularly good in Nevada, not-too-bad in North Carolina (a state without which it will be very, very difficult for Mr Trump to win overall) and close in Florida - though not so hot for the Democrats in Iowa, a state in which Secretary Clinton has struggled all year.

It's not all good news for Mr Trumps's opponents. African-American enthusiasm appears to be down. There's a large and unpredictable rise in unaffiliated, non-partisan early voting in some places, though as these Americans in some key places lean Democratic and are often pretty young, that might just confirm the overall picture. In general, if you'd offered Team Clinton those impressions a few months ago, they would gladly have accepted them. Now it's possible that the unlikely and marginal voters Mr Trump is depending on will turn up in person on the day, but it's not as likely as the 100% certitude that these early Democratic votes have already been banked.