One thing we know about public numbers is that they have

to be built up via art and artistry, as well as science. You don’t just go and capture them

in the wild, like they’re some form of easily-displayed and gawp-inducing new

specimen for the zoo. The next thing we know? Context is all. It’s the same in

every field. How big is that exoplanet? What does that mean in comparison to

the Earth? How big is the sun it’s orbiting? What might that mean for its

atmosphere, the potential for water on the surface, the likelihood of life?

One context is historical. Okay, economic growth looks

like it’s enough to keep unemployment low, but how fast or slow is it against

the longer-term averages? The usual level of growth since the Great Disruption of

2007-2008? The mean scores since the Second World War? Only then can you know

what you’re really looking at.

That’s why we look at election results (and opinion

polls) in the same way. It’s all very well being quite some way ahead, as

Labour were in the last Parliament, but what does that mean? We wasted our breath then pointing out that Labour had to rise quite a bit further before

they looked likely to win a General Election, and we probably still are, but

it’s worth a go. We’ll be returning to this theme in April, when we take our regular

look at how the Government and the Opposition are doing when measured against

the standards of the modern era (which roughly means since about 1970). But for

now, it might help to take yet another look at the Copeland and Stoke Central

byelections in a wider, longer – and statistically marginal, rather than binary

– context.

Now, stop us if you’ve heard this before. We know that we looked last time at just how bad these two results were for a serving

Opposition. There’s really been nothing like Copeland, especially, since on

some measures the nineteenth century. You could fill a page with words like

‘appalling’, ‘disastrous’, ‘humiliating’ and ‘catastrophic’. That’d be about the

measure of it. But that doesn’t seem all that helpful, to be honest. Anyone can

write a faux-Biblical and mock-ominous paragraph of doom. Believe us: we have.

But what is the exact scale and scope of Labour’s byelection performance, both

in Stoke and Copeland, and more broadly over the past couple of years?

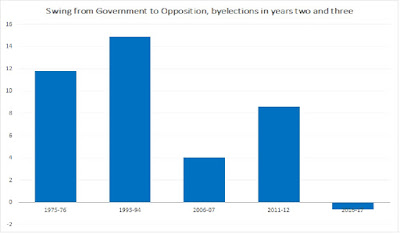

Here's where we can deploy at least some sense of

statistical clarity. This time, and for the chart above, we’ve looked at

various Oppositions’ byelection performances over the second and third calendar years of each Parliament. First, we’ve looked at the performance of those Oppositions that

were later successful in winning power: Mr Heath and Mrs Thatcher’s

Conservatives in 1974-79, John Smith and Tony Blair’s Labour in 1992-97, and

David Cameron’s Conservatives from 2005 to 2010. As a comparator, we’ve included the

byelection performance of Ed Miliband’s Labour in 2010-15: an Opposition that

appeared to be doing okay (but no better) in byelections at this point in the cycle, and was

competitive in the opinion polls, but which ultimately fell short when it came

to the crunch of a real General Election.

What do we find? Well, successful Oppositions should be hoping for big, big movements towards them. That’s not much of a surprise, but it’s nice to see it

confirmed in the actual numbers. Both Heath and Thatcher, and Smith and Blair,

were posting swings from the main governing party of over ten per cent – of

11.8% in the first case, and a spectacular 14.9% in the second. David Cameron

was getting some sort of swing at the same stage of the electoral cycle we’re

at now (approaching the halfway point), but it was much lower – at about 4%. It

won’t escape your attention, either, that the scale of those swings bore quite

a strong relationship to the subsequent full-scale election. Mrs Thatcher won a

modest but workable majority in 1979; Tony Blair triumphed in 1997, gaining

Labour’s biggest-ever majority in a remarkable landslide; David Cameron, who

wasn’t doing quite so well at this stage in terms of Westminster byelections,

had to settle for a coalition with the Liberal Democrats. At some point we’ll

try to write a full-scale piece about the formal relationship between these numbers and

General Election vote shares since 1945 (or encourage someone else to do it),

but for now we can just say that the bigger the swing at this point, the more

likely subsequent electoral success seems.

Clearly that doesn’t always hold. Ed Miliband was doing

better in 2011-12 than Mr Cameron was in 2006-07. You can enter all sorts of

caveats here. There were fewer byelections in 2006-07 than during 2011-12: there were just five such

contests in the former period, compared to the twelve held during Mr Miliband's second and third years as Leader of the Opposition. Three out of

those five battles took place on very unfertile ground for the Conservatives (Dunfermiline and West Fife, Blaenau Gwent and

Sedgefield). Even so, we should note that there’s clearly only a rough and

ready relationship between doing well in these elections, and then going on to

form a government.

So these comparisons aren’t perfect, or

always tightly predictive. However, and given Labour’s performance recently,

what they are is very suggestive. Over 2016 and 2017, there have so far been

eight Westminster byelections. and the Opposition has on average made no progress

at all against the Government. Indeed, they have gone backwards: there has been

a very small (0.65%) swing towards the Conservative Party. And things have got

a lot worse since Britain voted to leave the European Union. The swing to the

Conservatives is 3.9% since the summer of 2016, and an average of 4.35% in

Copeland and Stoke. The evidence is that Labour’s performance in these

byelections is steadily getting worse – just as its poll ratings have been

slowing deflating since the April of 2016. But it was anaemic, and deeply

concerning, long before that. The only place where Labour have even come close

to matching what remember was only its average performance under Ed Miliband is Tooting in June 2016,

where they achieved a swing of 7.25% towards them. Since we know from polling

and last year’s Mayoral election that Labour’s support has not retreated in the capital to the extent it might have done elsewhere, that’s yet another confirmation of everything else we thought

we knew from what data we have.

No Opposition in the modern age has

taken power without getting quite a swing towards them in Westminster

byelections held at this stage of the Parliament. No party has fully and

without help replaced another in Downing Street with a move towards it that was

below double digits. At the moment, the tide is flowing quickly in the other direction – just about as quickly, actually, as it was towards David Cameron in

2006-07. Don’t trust polls? Trust real votes. The picture is pitch black and still

darkening for Prime Minister Theresa May’s opponents, and they know it.