Monday, 23 December 2013

What can we expect for UK PLC in 2014?

The end of any year is a time to reflect. A time to recap. And a time to look forward. And that's what we're going to do today - reflect, rather than react.

2013 was the year that the British economy finally began to pull away from the black hole that the financial crisis of 2007-2008 had caused - and which was then exacerbated by the economic policies of the UK's coalition government. The level of growth which we actually got - of 1.3 per cent to 1.4 per cent, if we're lucky - was pretty rapid given that we entered the year fearing another recession. And now next year now bids fair to be pretty good - if we only look at the headline numbers for Gross Domestic Product overall. Every estimate now seems to push predictions upwards, rather than cut them - a depressing and salutary lesson in how little we know that we'd got used to for far too long. The doomsayers have been consistently proved wrong since about last spring, when a gentle but perceptible thaw started to take hold.

But it's not going to be the sunlit uplands. Sure, 'Public Policy and the Past' has probably been too gloomy about the prospects for Britain's economy up to now (though we always pointed out that her industries and businesses were more robust, in the medium term, than they looked). But the British economy remains fundamentally unbalanced - as it was always going to be, once Chancellor George Osborne made the decision to cut back the public sector so rapidly, and to rely on massive increases of private debt to take up the slack.

The result, especially once the Government adopted its apparently growth-at-all-costs mantra late in 2012? Well, it's what everyone knows in their heart of hearts: what even Mr Osborne's colleague and Business Secretary, Vince Cable, calls a raging house price boom in the South East of England, unmatched by similar prosperity elsewhere. And, at one and the side time, a really horrible record on productivity and exports, both figures which seem to look worse every time we look at them. And endless, endless public sector cuts - all the way to 2018/19. Let's imagine the British economy like this: a reluctant diver, it has finally left the podium to try to slice into the water after a lot of shivering and dithering, but it's arcing through the air with a bent neck and back that'll see the body smash and shatter when it reaches the pool. The next Parliament will be a time of continuing economic pain, especially as interest rates are now likely to rise pretty quickly after the General Election of 2015 - if they haven't already, to career-ending effect in Mr Osborne's case.

So the prediction for 2014? More unspectacular but gently accelerating growth, tugged along by a more and more buoyant United States. More below-inflation wage growth for nearly everyone, until right at the end of the year (or not at all). A strenghtening, but still below-par labour market that struggles to deliver any improvements in Britons' standard of living. All in all, it'll be a situation which will see the main governing party, the Conservatives, continue to cut into and erode Labour's rather fragile lead in the polls - though perhaps not by enough to be confident of returning to Westminster as even the largest Party after May 2015. The macroeconomy will look positively healthy by recent standards; normal citizens will still feel poorer.

None of which is very earth-shattering in terms of punditry, really. But it's at least a welcome return to some sort of normality after the last few years - and the occasion of at least half a glass of Christmas cheer.

So that's all for now. We'll be back in 2014, to talk about the impending General Election (of course), the economy (naturally), and any continuing public policy debacle that might have been avoided had a friendly historian been on board (and yes, we do mean you, Mr Duncan Smith). Look for new posts from Monday 6 January, and you won't go too far wrong.

Meanwhile, Happy Holidays!

Tuesday, 17 December 2013

The Ashes: sometimes, the day just goes against you

England's cricketers have relinquished the Ashes as quickly as they could. Old enemies Australia (above) are cock-a-hoop, and they're rightly ecstatic that their long losing streak has finally come to an end. A proud and patriotic people, deeply invested in their sports and teams, getting kicked around the cricketing world was just no fun at all.

Now an inquest will start. It'll have to, because England have been beaten so badly, and so quickly, that nothing else will do. Already the dread words 'deep-seated', 'malaise', 'domestic game' and the like are being bandied around. Suddenly tinkering with the county game is the problem. Or the tedious go-slowism of England's conservative and non-attacking top batsmen. Funnily enough, no-one was saying any of that six months ago.

Regular readers will know that Public Policy and the Past is sceptical about these sorts of explanations. It's difficult to tell where structure ends and agency begins, of course, but in a game like cricket - which is all in the mind of the players, and all in the momentum of any game or series - we're all in favour of agency here.

Remember that, even this time, Australia had a really bad first day in this series. When a visibly nervous Mitchell Johnson came in to bat during the First Test in Brisbane, they were tottering at just 132-6. A few whacks later, and the next day's fateful leg-slide flick by Jonathan Trott that got him among the wickets, and things looked utterly different. The Australians looked like they didn't know what to think until they got some breaks - like the three tosses they won to bat first three times in a row. Had England taken their catches on day one of Adelaide's Second Test, the result might have looked pretty different there too. The visitors wouldn't have spent all those punishing hours in the field. They wouldn't have started to pine for the dark evenings and Christmas lights of home - or just about anywhere that wasn't full of jeering opponents. England got some tough breaks, as well as coming up against some tough opponents.

Don't take it that PPP is saying that it was all about luck rather than judgement. This debacle had probably been coming for a long time, especially since Australia did so well in coming back into last summer's Ashes following their humiliation at Lord's. The signs have been there for a long time - if people have wanted to see them. But the humiliation, the burn-out, the grind-your-faces-into-the-dust level of defeat? That's probably down to the sequencing as much as any so-called 'underlying' causes. Oh, and the individual misjudgements of batsmen who were subject to a slow-motion landslide that needed a few pebbles, somewhere - almost anywhere - to get it going.

You know what? Sometimes it's just a bad day. Or fifteen.

Monday, 16 December 2013

Real wage rises might save the Government

Sometimes it's hard to see a route to re-election for the present UK government. The economic winter has been long and cold; left-leaning voters have defected from the Liberal Democrats in their droves, gathering around Ed Miliband's relatively left-wing rhetoric, while the challenge of the United Kingdom Independence Party shows little sign of going away.

All in all, there seems little respite for Britain's governing Conservatives, who have lagged in the polls for two years now. But there is one single chink of light: rising real incomes, which might save them in the medium term. Macroeconomic numbers have been telling us for some time that Britain is on the mend, but now it's becoming more and more apparent on the ground. House prices are likely to surge ahead next year; the construction industry is growing quite rapidly again; every economic update seems to upgrade Britain's growth prospects. That might not be that sustainable - it looks for all the world like yet another house price boom - but it will last us for this Parliament, that's for sure.

This will definitely have political consequences, and it may help the Conservatives to carry on in office - as a minority, perhaps, but power is power. American political scientists have long looked at real disposable incomes, rather than macroeconomic indicators such as unemployment and inflation, to explain election results: some recent work has suggested that President Obama's 2012 victory was partly down to voters' wages growing in the months leading up to the November 2012 contest.

And the main personal finding of recent work by the Office for Budget Responsibility? That Britons' incomes will start to go up in the last few months of 2014, before growing more quickly just before the upcoming General Election of 2015.

Things might look bad in No. 10 Downing Street right now - but as regular readers will know, 'Public Policy and the Past' has long been unimpressed by Labour's performance in local government elections, and in the polls. There will be a swingback - there always is. Mrs Thatcher looked in dire trouble in 1982 and 1985, only to storm back to victory two years later.

That might not happen. But the Government still has a good chance, if the OBR is right about wages. If incomes continue to fall, of course, they're toast. But the outcome of the next General Election is still uncertain. That's easy to say, and hard to feel when you look at such apparently stable polling. But it's where we still are now.

Thursday, 12 December 2013

The curious case of the generous Chancellor

Amidst all the talk of continuing budget cuts and austerity in last week's Autumn Statement, delivered again by Chancellor George Osborne (above), there was one curious giveaway: an announcement that there will no longer be any limit on the number of students universities can admit. Now, the fact that such a barrier still existed will have been a shock to any members of the public still convinced of the old, silly myth that governments had pressganged ever-greater numbers of young people into Higher Education when quite the opposite situation has pertained for many years. But I digress.

The real shock here was twofold. For one thing, the Government had been privileging 'top' universities in its progressive liberalisation of the sector's controls on numbers, allowing them to take unlimited numbers of students with ABB or higher at A-Level. Now it's 'reverse engines', and everyone can have as many students as they like: a concept met will ill-disguised fury from the Russell Group of the most selective institutions, and the cause of much shock and confusion among academics and administrators.

But more importantly for a blog on public policy, the real question mark must be: why announce this now, when it's so expensive? The Government's new student loans system is already set fair to leak 40 per cent of all its initial outlays, and that figure will probably rise until nearly half of all the money shelled out by the taxpayer never comes back in student loan repayments. And the Department of Business, Innovation and Skills has recently had to slam on the brakes over private college expansion and European Union student finance because it's so strapped for cash.

The answer? It appears that the Treasury think that the sale of the remaining parts of the old student loan book will plug the gap - except that of course that'll be a once-and-for-all sale, which will only support the extra monies flowing into universities up until 2018/19. Neither do we really know what the net income to the Treasury will be once we tot up all the future losses involved in foregoing all those repayments. The Treasury appear to have made a series of elementary accounting errors there, by the way, which we will ignore for now. You'd think it was impossible, except after the spreadsheet debacle over Virgin's West Coast mainline train services bid, almost anything seems believable in Whitehall these days. Anyway, the headline here is simple: after 2018/19, the taxpayer is on the hook for yet another £700m of spending following last week's announcement.

Another thought? Well, just selling off the loan book can't be all there is to it. Not even this profligate government could possibly be so incompetent. There must be a long-term plan to constrain costs in the back of the cupboard somewhere. 'Public Policy and the Past' would suggest that the funding hole will be met in two ways: firstly, a complete liberalisation of the market in Higher Education after the next election, designed to drive down costs (except that it wouldn't, but that's another story). There'll be a massive expansion of private colleges, which might well in the end drive spending upwards, but there you are. Maybe the Russell Group will be allowed to charge what they like (up to, say, £24,000 per year in some subjects) and still get access to state sector research money, even if they would then have to be barred from the state loan system for undergraduates. And, more importantly, there will almost certainly be a revision of the post-2010 university finance system, already underway at the margins for poorer students. Interest rates on the loans might be raised, or the repayment period shortened. Only then does this move make any sense.

Otherwise, the puzzle of the generous Chancellor will hang in the air for some time to come.

Sunday, 8 December 2013

Nelson Mandela and the art and craft of the historian

The passing of President Nelson Mandela has made many people reflect about many things: the nature of leadership, of rhetoric, nationhood, race, and politics itself.

Historians have got a lot to add here. As Richard Toye of the University of Exeter has reflected, one thing we can say is how complex things seemed at the time, bringing to the question a degree of fine detail and a sense of contestation that might be lost if we celebrate a totem and an image rather than a man. Mr Mandela was opposed by many, in his own country and beyond. He was a politician, not a saint, and he used cunning, rhetoric and sometimes force to move towards his objectives. We have to look forwards, from the perspective of a deeply divided South Africa as it existed in the 1980s and 1990s, rather than just backwards from the more united and fairer society that Mandela forged.

What we historians might also highlight is the admixture of structure and agency which makes up changes in our history - and the way we professional historians try to deal with them.

Consider the situation when he walked to freedom from his prison cell in 1990. A sinister security infrastructure was quite happy to stir up the prospects of a civil war. The ANC was faced with enemies on every side, and had it lashed out in angry vindication the whole structure might have come tumbling down in an all-out confrontation that would have left the region devestated. Nelson Mandela's words and deeds - who can forget 'take your weapons, and throw them into the sea'? - helped to stop that happening. In President Obama's memorable phrase, he 'took history in his hands'.

Now things may not have been as bad as they seemed. The end of the Cold War and changing views within white South African society meant that the governing classes of the time had few other places to turn. But their erstwhile opponent made it easier for them - and for the ANC's other enemies. He provided them with a respectable face to bargain with, and a set of ladders to climb down.

Where will the balance between the individual's role in history, and the logic of the situation, be struck? What will future historians think of the agency and the structure? We don't know yet - but we know, at least, that we will have to know.

Friday, 6 December 2013

A bizarre Autumn Statement

This year's Autumn Statement on the economy, as delivered for the fourth year by Chancellor George Osborne (above) was a right old curate's egg affair - a mix of the good, the bad and the downright ugly (if you'll forgive two cliches in one sentence).

On the one hand, the economy is growing again - rather rapidly, in fact, though actually the Chancellor very slightly revised down official growth forecasts for 2015-17. That'll leave him plenty of room to talk about a boom in a May 2015 General Election, of course, and the lacklustre reply of the Shadow Chancellor, Ed Balls, will have cheered him no end as well.

So is the Chancellor similing? Probably not, no. Because when he announced that he wanted to 'rebalance' the economy, and lauded 'the march of the makers' - aspirations he still mouths, though less and less convincingly - he didn't think that productivity, investment and exports would do so, so badly.

The impression lingers that this isn't the recovery the Chancellor wanted, and that he's grabbed at Help to Buy and a debt-driven consumer binge to get himself out of the hole he himself dug. Just like the Conservatives did in 1954-55. And 1963-64. And 1986-87. Etcetera. The Office for Budget Responsibility now thinks that ridiculously buoyant house prices will shoot up even faster than they thought a few months ago, and that personal debt will go up more quickly at the same time. That's because real wages are going to continue to stagnate or go down, and Briton's won't be borrowing to make themselves feel good: they'll be running down their savings rate to pay their bills. All at a time when austerity as executed by public sector spending reductions won't do anything to put wind in the economy's sails: for the Government is going to speed up spending cuts, not slow them down as we get closer to balance in the next Parliament - leaving the public sector smaller than it's been for two or three generations.

It's a recovery, but it might be a voteless one - akin to the Wilson government's 'recovery' in 1968-70, which eventually led to Edward Heath defeating Labour at the polls in 1970, or the even stronger growth of 1994-97, which ended in disaster for the Major Conservative government of the time. Half of voters seem to think that the Autumn Statement was bad for an economy they increasingly define as their own household budget and outgoings. It's hard to come back from those sorts of figures.

Growth, yes. Victory, no.

Thursday, 5 December 2013

The great badger cull disaster

So the badger cull in the South-West of England has been called off, hopefully for good. Natural England has finally pulled the plug, after many months of being told - by the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, among others - that it just wouldn't work.

Ministers set out to kill enough badgers to stop the spread of the tuberculosis that many of them carry through to cattle. It's a terrible disease in livestock, and it causes thousands of fatalities a year. Had the killing worked - if it had ever looked likely to work - a culling programme would probably have been justified. But first the Government ignored all the evidence that shooting badgers has never made any difference to overall disease levels. Then it said that it wasn't going to do any follow up studies or scientific work on the cull at all - so that the limited killings, in only one part of England, wouldn't have any wider applicability whatsoever. Then it failed to get enough of the badgers killed to reach the threshold where culling would do any good anyway, even in the very tightly-drawn boundaries of the test area or the local region.

In the meantime, many hundreds of beautiful, healthy, inoffensive animals have been slaughted. The Government has blown millions of pounds of your money, to absolutely no effect. And killing the healthy animals that marksmen could find, allowing diseased animals to move into their ranges and disrupting a settled situation, has probably made the TB problem worse.

What a disaster. And it's not alone, either. Universal Credit has become a laughing stock. Higher Education tuition fees in England have managed the trick of asking both taxapyers and students to pay more, without giving universities much more money. The Government has to do better soon - or its chances of re-election, even as a minority or in a coalition, will be gone.

And let 'Public Policy and the Past' get this straight: this bungled cull is now, and always was, blinkered, nasty, disgusting, immoral and wrong. The word 'fiasco' doesn't cover it, and all we get out of the Ministry in response is a bland press release. In any honourable world, the Secretary of State - who so memorably said that it was the badgers themselves who had 'moved the goalposts' - would resign immediately.

But of course we don't, and he won't.

Monday, 2 December 2013

The drinking water myth

So we all know that you should drink quite a lot of water to stay healthy, right? It reduces the strain on your kidneys and your bladder. It's good for your bowel. And your skin. And it stops you getting 'dehydrated'.

Well, regular readers will recall that I'm writing a book right now on 'The Politics of Water in Post-War Britain'. And I'm afraid to say that - just as most people didn't smell that bad, despite only having a bath once or twice a week - we don't appear to need that much water after all. All those cups of tea and coffee that people drank instead during the 1950s and 1960s? That might have done just as well.

So where did the idea come from? Well, it probably came from three, relatively interconnected, historical sources: the first, state-driven attempts to make us 'better', and 'healthier', partly so that we could ward off foreign menaces and serve the warfare state of the 1940s and 1950s. It does look as if the US National Academy of Sciences was the source of the idea (registration required), in a not-very-well-sourced set of 1945 recommendations. The second reason? Bottled water's attempts, from the 1970s onwards, to persuade us that it's 'purer' and 'better' than tap water - though it isn't, of course. A third reason for the rise of this concept, which has seen everyone marching around with plastic bottles of water even though they don't feel thirsty, is an increasing food festishism and faddism related to the way in which we eat food. Hunger? Seasonality? They're almost gone, relaced by a set of food-as-lifestyle indicators that are supposed to say more about who you are than how you feel. Bottled water makes you look healthy, fashionable and busy: you'd better get it down you if you want to look like a top sportsman or woman. Even they don't need quite so many bottles of isotonic sports drinks as they're told, but still.

Sure, if you're going to the gym a lot, or sweating it out in some hot climes, you should in all probability get a couple of litres in you a day. And it's better than guzzling down all those calories in fruit drinks. Otherwise, your body will just retain more of what you've got - and you should be more than okay. You can get most of the water you need from the food you eat anyway. Get plenty of fruit and vegetables and a couple of glasses of water in you every day, and you'll probably be fine.

That's it for today - not much of a public health announcement, but enlightening about our mythic 'knowledge' and common sense, all the same.

Friday, 29 November 2013

Boris Johnson and the science of IQ

Boris Johnson's recent speech on equality and intelligence helps to show why those in the know rule him out as a future Prime Minister. He might be witty, interesting and above all able to cut through to the public in the way few other public figures can. But he's also a fly-by-night tightrope walker who makes it up as he goes along.

So it is with his mayoralty. So it is with this speech.

Boris (above) posited that there can't be a greater or wide measure of equality in our society because citizens have different levels of intelligence, as measured by their IQ scores. Well (deep sigh). Well. Well. Where does one start with this particular misunderstanding of just about everything that's been written on the question for the past thirty or forty years? It's not that it's elitist - though, as the Deputy Prime Minister said in reply to Boris' rant, it certainly is. Were one to show that there was an ineluctable link between academic ability and achievement, one might think that a bit of elitism in terms of written schooling might be justifiable, if not particularly helpful to the eighty to ninety per cent of children who'd be left out of the grammar school education Boris has been calling for.

It's not that. It's that his science is just so, so wrong. People are of course born to be different. Their height, speed, capacities and acuities are different. So far, so good. But the idea that there is a fixed leve of something called intelligence - well, here there's a parting of the ways.

So here's a thing that Boris didn't say: IQ tests are a joke. Their results shift around all over the place, with children gaining very high and very low scores across time, the same child racing ahead of the IQ 'average' one week and behind the next. There is no one fixed and unchanging quality called 'intelligence'. Here's another point he must know, but chose not to make: they measure a certain type of inside-the-box logic chopping, rather than true intelligence. Want to group things of a certain type together very quickly? Do some rapid maths in your head? Fine. IQ's for you. But if you want a truly testing, questing, flexible, reflexive and creative type of learning - like that the Chinese and Singaporese increasingly worry that their rigid education systems miss - you'll want to throw those tests in the bin and start again.The whole point about the 11+, the out-of-date and derided British exam that relied on IQ, is that civil servants were forced to concede that it had been discredited very rapidly after the 1944 Education Act that helped to enshrine it in British culture.

Here's some more points: there's no evidence that what IQ numbers we do have are related to those of parents. There's nothing to support the idea that IQ is correlated with economic success - quite the reverse, in fact. There's lots of evidence, on the other hand, that IQ-based systems privilege middle- or upper-class ways of speaking and reasoning, rather than the different types of knowledge prized by other socio-economic groups. And that politicians like to stigmatise people of 'low intelligence'. Mrs Thatcher's intellectual svengali, Keith Joseph, did just that in 1974 - evoking a row about the 'underclass' that reverberates to this day. Boris is tipping a cynical nod and a wink to a constituency he knows he'll need if he's to storm the ramparts of his party, and then No. 10 Downing Street.

But if the intellectual case was 'inequality is fine, because it reflects ability' than every single step of that argument is just wrong. False. The opposite of opinions based on evidence. Grounded in nothing. Nada. Squat. Zip.

Perhaps the Mayor of London should do his research before he starts talking - or, just perhaps, exhibit a little more intelligence.

Wednesday, 27 November 2013

Hurrah for 'Doctor Who'!

If you're reading this in the UK, and you haven't heard that this month marks the fiftieth anniversary of the long-running science fiction serial Doctor Who (above), then you've been living under a rock. The BBC has spun itself like a top in endless promotion of perhaps its most iconic and famous show; fans have been driven into ever more fevered paroxysms of speculation.

But it's worth reflecting on what the ever-regenerating, ever-changing, ever-shifting Time Lord has given us over the years since Verity Lambert and Sydney Newman put the Galifryean on our screens. He's been there for most of all our lives, apart from a long, long hiatus between 1989 and 2005, broken only by a 1996 TV Movie. He's thought about and faced the problems of our age, and shown us our society in a mirror that we didn't always like - but which was always meaningful, always sharp and always important.

Have a think. Have a flick back through the back catalogue, and consider the way in which our problems have involved the Time Lord's adventures. There's been the threat of robots taking us over the brink of war, long before Wargames and Terminator in the 1980s (The War Machines, 1966), militarism and the First World War, the same year as the film adaptation of Oh, What a Lovely War! (The War Games, 1969), worries about cybernetics and humankind's artificial 'enhancement' (Tomb of the Cybermen, 1967), ruminations on genocide and ethnic cleansing (Genesis of the Daleks, 1975), the nastiness and solipsism of the 'leisure society' (The Leisure Hive, from 1980, and Vengeance on Varos, from 1985), and finally the madness of the Cold War (Warriors of the Deep, 1984). There were even some great big green worms, unleashed on the Third Doctor by a sinister corporation called Global that was busy pumping out pollution that would soon threaten the world with a great big wave of slime (The Green Death, 1973). Nasty stuff - and totally in tune with the apocalyptic environmental fears of early 'seventies Britain.

The revived series had carried on where the old one left off, going back to think anew about the Cold War (Cold War, 2013), genocide and ethnic cleansing (Dalek, 2005), the nature of justice and revenge (Family of Blood, 2007), genetic engineering (The Lazarus Experiment, 2007) and even urban planning and city life (Gridlock, 2007).

That's one of the reasons we love it all so much. Not just because it's a great big dinner of adventure, excitement, mystery and space travel, with a side order of nationalistic British flag waving to boot. Yes, that's all great. But what's really important is how the Doctor has made us think - and feel - about ourselves for a long, long time now.

Let's raise a glass: hurrah for Doctor Who!

Monday, 25 November 2013

Jonathan Trott, everyman

Jonathan Trott's departure from England's cricket tour of Australia must touch at the heartstrings (above). A dedicated man, immersed in his sport, and famed for his physical and mental toughness in the middle, has been brought low by a 'stress-related illness'. That might mean many things, but right now it means that Trott is hurting. A lot.

We've been here before, of course, for instance when Marcus Trescothick was forced to come home in 2006. But cricket fans and commentators are starting, just starting, to get a handle on a problem that's been dogging the game for years: the black dog of depression. Former captains who were rather too quick with their criticism have apologised, mortified to hear about the problems they've probably exacerbated.

Now, the statistical underpinnings of the idea that cricketers are more prone to depression (and suicide) than the rest of the population are open to question. But there's no doubt that professional sport as a whole exposes men and women to nearly unbearable pressure. Do you fancy your entire professional identity and ability coming undone in front of tens of thousands of people - with many millions more watching at home? No, neither do I.

But there's no doubt that progress has been made, both within a rather conservative game, and in our wider society. Graeme Fowler, who played for England back in the 1980s, has spoken with some bravery about his own battles with depression - struggles that wouldn't have met nearly such an understanding or sophisicated response as they do today. We've come a long way. Senior figures within the game are now just about able to talk about their own 'demons', problems, doubts, worries and fears. We need to go further, because we've basically just come out of cavedwelling ignorance and started talking about depression and anxiety as if they're the same as having hurt your leg. But it's all a start.

It's be nice to think that people might stop hurling ridiculous insults and threats at each other while they go about their business - and hold back before they call each other names. The hosts might look at themselves a little quizzically after this. Quite apart from anything else, Australia's big and aggressive talk before the game nearly came unstuck on day one of The Ashes - and their opponents might regroup and stick together even more tightly now one of their number has been wounded. It's probably a forlorn hope, and we'll probably all be back whacking each other with a little cricket stick in a few days, but hey - it's something to hold onto.

For now, it's worth saying this: lots of people are struggling all the time. It's impossible to live without feeling like you might come apart. You have felt that. I have felt that. Everyone has felt that. Maybe there's someone struggling next to you at work right now. Why don't you ask them? Why don't you talk frankly about your own problems if they ask you? One thing's for sure: the principles of World Mental Health Day - frankness, fairness, compassion, dignity, openness - have never been more relevant.

Friday, 22 November 2013

Remember John Kennedy today

The fiftieth anniversary of President John Kennedy's assassination in Dallas, Texas, is an opportunity to reflect on what it means to govern, or to be a leader, or to try to effect policy changes, in the modern world. The image of JFK (above) has often obscured more than it has revealed, for his personality seemed so dazzling to so many at the time (and since) that any historical insights about how he actually governed seem to have been blotted out.

Start with this: he was confident in his own abilities. Rich, tall, handsome and magnetic, he was difficult to know - but self-assured and self-reliant enough to ignore what the 'experts' told him. Many of his military chiefs advised an immediate military strike at the beginning of the near-fatal Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. Kennedy ignored them, allowing his Soviet adversaries to climb down the ladder he offered them - the secret removal of Jupiter missiles from Turkey.

Continue with this: he looked like he knew what he was doing. Through all the affairs, all the constant, compulsive womanising, all the pain from his back, all the chronic illnesses and all the pills, he stood up, smiled, walked and talked like you should follow him. And many did. He understood the power of the image. But it was more than that. He understood (like the present incumbent) that the power of words has not passed away in the era of the big state and the big missile. Indeed, it has become ever more important to give and shape meaning in an ever-more complex world. His extraordinary inaugural address, which has gone down in twentieth century history as the very acme of what a speech actually is, is only one example.

End with this: he understood that you can't get rooted in one political community or one outlook. That can be an intellectual prison - especially for a chief executive, who has to take all arguments and disagreements unto himself for resolution. He talked tough on communism - while trying to negotiate the superpowers away from the brink. He defended the value of the dollar (appointing a Republican to be his Secretary of the Treasury) while trying to break out of the relative economic stagnation of the 1950s. He vacillated and hesitated on civil rights, before finally beginning to move towards the only viable solution - desegregation.

Catholic realist that he was, one of his purest insights was that attempting to erode darkness by degrees, and working every day towards apparently impossible goals, was and is as important as actually arriving at any destination. As he put it at his American University address on the 1963 Nuclear Test Ban Treaty:

While we proceed to safeguard our national interests, let us also safeguard human interests. And the elimination of war and arms is clearly in the interest of both. No treaty, however much it may be to the advantage of all, however tightly it may be worded, can provide absolute security against the risks of deception and evasion. But it can... offer far more security and far fewer risks than an unabated, uncontrolled, unpredictable arms race. The United States, as the world knows, will never start a war. We do not want a war. We do not now expect a war. This generation of Americans has already had enough - more than enough - of war and hate and oppression. We shall be prepared if others wish it. We shall be alert to try to stop it. But we shall also do our part to build a world of peace where the weak are safe and the strong are just. We are not helpless before that task or hopeless of its success. Confident and unafraid, we labor on - not toward a strategy of annihilation but toward a strategy of peace.

There is little more to say than this: remember the strategy of peace. Remember President John F. Kennedy today.

Monday, 18 November 2013

Grammar schools are not the answer to our problems

Sir John Major's emergence as a new-old type of 'Red' Conservative is a curiosity of our era. Serious-minded, experienced and worried about the type of grey, hidden and grinding poverty often found in our near suburbs, his is an expected but not-unwelcome (re-) eruption into our public life.

This time he's gone for the dominance of the privately-educated in our public life - which, if we look at the Cabinet or the top professions, is indeed just as 'shocking', troubling - and damaging - as he says.

The remedy some seize on, though, is a completely ahistorical fantasy. The cause of the grammar school is being heard again in the land, full of mendacity and historical ignorance about the 'opportunities' granted to 'the bright' by the existence of a test sorting the clever sheep from the not-so-clever goats at the age of 11 or 14. It was the 'system' that was adopted in England and Wales between the 1944 Education Act and the Government Circular announcing official disapproval for the idea which went round in 1965, but which took about a decade to bring this division to an end across most of the country.

It's an idea that's gained a bit of traction in recent months, with the United Kingdom Independence Party taking up the idea, various right-wing commentators writing that the end of selection was only one symbol of the end of meritocracy and our hard-and-fast aspirations to actually greater real knowledge, and even left-wing commentators making clear that selection by house price (given the premium paid around 'good' schools) isn't much of a replacement.

Memo to everyone: grammar schools didn't work by encouraging social mobility.

We only have to look to areas which still have them - Kent, for instance - to find schooling systems much more divided than elsewhere, much more scarred by the use of private tutors, and much more divided by social class than areas dotted with comprehensives.

But we can look historically at this question too. You'd expect me to say that, but studies of children born in the 1950s show absolutely no social mobility premium for areas with grammar schools. We have lots of official evidence from the 1950s that children from poorer backgrounds who went to grammars were much more likely than others to drop out. And it's much more likely that the rising economic tide of the time - and increased equality - helped people escape poverty, rather than the few Latin lessons and blazers handed out to a lucky handful.

You don't have to believe me. You can listen to two (actually very conservative) officials bemoaning the division of the school system at the time, revealed in their private correspondence in (ahem) my new book, published last year:

This country is pouring out its human wealth like water on the sands... A system under which failure to win a place in a selective school at 11+ meant complete and irrevocable denial of the coveted opportunities associated with a grammar school education could not hope to win the support o fparents, and could not survive the day when their wishes could gain a hearing.

Want to pour out our human wealth on the sands? Go ahead, build some more grammar schools. Otherwise - make universal secondary education to sixteen (and now eighteen) work properly. As someone once said: there is no alternative.

Friday, 15 November 2013

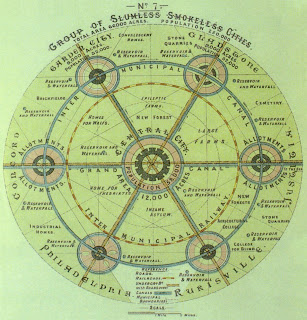

Wanted: new garden cities

The news of a new Wolfson Prize for the best new Garden City ideas is welcome indeed. The concept of Garden Cities (above) represented the best of Edwardian social reform, an ideology of national progress that cut across political Left and Right and focused on the health, happiness and dignity of working people. They were to be 'light' and airy, bringing parkland into the heart of the town while spreading small but proud semis out along rivers and lakes. Providing work, shops and amenities in their peripheries as well as their centres. Allowing normal people to aspire to live a life previously available only to the privileged few. That's a far cry from today, of course, when central government seems hell-bent on stigmatising local authority tenants as 'over-occupying' spare rooms they might use as studies or stores, but there you are. The money's on the table. Have a go if you want to.

The real reason we need to think about such new-old spaces is that we have to build more houses. Many more houses. Think: tripling or quadrupling our output. Now. This minute. Look at the numbers: building one million more homes in the next five years will only keep up with demand. At the moment we might 500,000 to 600,000 if we're lucky. At a time when most articulate young people are coming to realise that older generations have grabbed all the deckchairs, doing anything else would shortchange anyone under the age of thirty to an entirely unacceptable degree.

What's happening on this front? Well, the Prime Minister's entirely well-intentioned announcement that new towns and cities were on the way has just been quietly junked. Mainly because Conservative voters in the South-East of England - mostly over the age of thirty themselves, of course - don't like the idea. And everyone else can just live in vastly over-priced boxes in the middle of nowhere, thank you very much.

That's a mindset that will just have to be ignored in the years to come. It's as simple as that.

Now don't think that 'Public Policy and the Past' wants all our green spaces just concreted over. There's no need - especially when golf courses cover more of Britain than housing does. Such spaces could be contained, as the post-war New Towns were. No-one thinks Harlow is about to eat all of Essex, or Crawley Sussex. A new generation of garden cities could be high-density, high-public-transport, bike-laned adornments to our society. They could be visceral, surprising, winding, new-old places for us all to meet, greet, charm and chat - along the lines of Lord Richard Rogers' Towards an Urban Renaissance, published in 1999 but never paid more than lip service in the intervening years of toy-build and low-build.

Come on. Let's build a new city between Oxford and Swindon, between Swindon and Bath, and between Leamington and Oxford. Then let's build more - between Stevenage and Bishop's Stortford, and between Bishop's Stortford and Chelmsford. For a start. Because that's what it's going to come to in the end, and if we start now, we can manage and control the building so that we're proud of it.

We face a housing emergency. We need whole new cities. We can build them interestingly, vividly, brick-by-brick, square-by-square, wiggly line by zig-zag terrace. But we need them desperately. And we need them now.

Wednesday, 13 November 2013

HS2: mind the numbers gap

This blog has always been a great advocate of looking beyond the surface of any numerical claims. That's because they're hard to understand and interpret. But it's also because they're made up. In the best sense, of course, in that you've got to build them up from other numbers - with different meanings, provenances, orders and structures.

It's the same with all the claims and counter-claims about High Speed Rail 2 (above), which is supposed to take very rapid trains north of London, to Birmingham, Leeds and Manchester, in two stages over the next couple of decades.

It's probably - just about - still worth building. No doubt the Great Western to Bristol looked like a big gamble when Brunel laid it out. But it worked - and it still works, with essentially the same line carrying tens of thousands of people a day. The chance to build this kind of infrastructure comes along only once in a lifetime - and in HS2's case, perhaps once every several lifetimes. It will serve as a workhorse of British travel for many, many decades, meaning that the money spent might still be worth it. If its costs keep rising, it might one day be time to pull the plug. That moment doesn't seem to have arrived yet.

But the thing that we can say right now is that you should beware of the traps involved in taking all the claims about its economic benefits too seriously. These have been officially revised down now on so many occasions that it's not worth even putting up all the links. And why? Because the business case rests on lots of assumptions that you might or might not want to make. About how much the time of leisure and business passengers is worth, and the relative merits or demerits of upgrading other lines. About how much work business passengers will be able to do on wifi-enabled trains and on their smartphones. About growth in provincial cities, and indeed the economy as a whole. About the true costs of planning blight. About the mulitipliers to apply to the building work in the first place. And so on - and on. You can plug the data in and get pretty much to where you want to go - which helps to explain the confusion and the doubt around this project, and many others.

It's a pity, really, because it's these indeterminacies that allow the scepticism about everything and anything government tells us to continue growing - an increasingly powerful force in our politics that at first appears far from the apparently-prosaic realities of a train line. It doesn't help that the Government made such a comprehensive mess of the renewal of Virgin's train franchise, in a Yes Minister-style foul-up involving a junior civil servant typing the wrong values into an Excel spreadsheet. But the real challenge to our public policy is far deeper: how can we even discuss our collective choices when even the basis of the numbers are now so complex - and so contested?

There isn't a technical answer. There's only a philosophical and, at one and the same time, a practical one. It's called politics - the art of choice itself.

Monday, 11 November 2013

Getting it wrong - and getting it right

Show your workings. That's what we tell students, in pretty much every discipline that we academics teach. And why? Because if they don't, neither the student nor the teacher knows where the calculations have gone wrong - or where the arguments have gone awry.

And when you can see where you went wrong, you should be able to pinpoint where you could go right next time. So welcome, then, to four times that 'Public Policy and the Past' got it wrong. Forget getting it completely right about Universal Credit: sometimes a mess-up is just as instructive.

1. President Obama's re-election might be a very, very narrow one. A relatively left-wing president (above). A listless and only slowly-recovering economy. A fired-up opposition, with a candidate tacking towards the electoral centre just as fast as he dared. A recipe for a close one, right? Er, no. Sorry about that. In the end, when all the fuss had died down, President Obama was re-elected pretty easily, dropping only one state that he had won in 2008. The lesson? He got out his voters. His team used all the numbers and techniques available from quantitative social and economic sciences - and all the grass-roots force of community activism - to reach every single voter they could. And they damned the Republicans and their candidate for being a throwback to the bad old days. Ed Miliband's Labour Party has taken the former lesson to heart; the Conservatives will try to utilise the second in 2015. It's going to be a close run thing between them.

2. Tuition fees at English universities would put off large numbers of poor students, who would look askance at the huge sums involved. Well, no, not really - or not yet, anyway, at least among full timers. If fees rise successively to £20,000 or more, then overall numbers might fall. The real underlying problem with the new tuition fees scheme in England has always been that it's completely financially sustainable, will land the taxpayer with nearly as many costs as the old one while lumping debt onto the younger generation, and doesn't provide universities with more money even while it charges everyone more. But 'Public Policy and the Past' also thought that £9,000 a year would sound like a lot. It hasn't sounded like enough to put large numbers off. The conclusion? Younger people know what a good investment Higher Education is; but even more clearly, we are still going through a cultural revolution, familiar throughout the developed world, which is making post-18 education an assumed norm, rather than an exception. That's a powerful reminder of how much things have changed since the 1960s, when only a small slice of younger people went to universities.

3. Greece would exit the Eurozone. Greece is still in a mess. It's still getting worse, out in the real economy where jobs, cash and even basic drugs are scarce - even if the Government's borrowing is now beginning to come down. It will go on for years. The crisis may even threaten the existence of Greek democracy. The answer? Well, normally you'd go for the three 'Ds' - default, devalue, deflate) - or at least a mix of them. Iceland has bounced back pretty quickly from its brush with economic death. Argentina came back strongly from its early 2000s crash. This blog has always thought that's what will happen in the end. But Greece can't go down that line. Its Eurozone partners won't let it. And, after last night's failed vote of no confidence in the Athens Parliament, it's clear that her politicians won't force the issue - at least for now. The lesson here is simple: political commitment to the Eurozone, the fear of chaos if bits of it start to break off, and the power of northern Europe's creditors (particularly Germany) are all more clearly intact than we had thought. The European Union and the Eurozone are staying together - for now.

4. The 'Help to Buy' scheme turned out to be a mouse. Banks were quite happy to take taxpayers' money to subsiside mortgages - at a price. The price was very high interest rates on 'Help to Buy' deals, which involve the Government standing behind the deposits of buyers who can't reach the 20 to 25 per cent of houses' value that risk-averse banks want you to slap down on the table these days. This seemed to mean that the scheme would be a bit of a damp squib. Why borrow at between four and five per cent, when you could wait for a year, save more, and borrow at two per cent? Well, the quite rapid takeup of this scheme provides the answer: the many twenty- and thirty-somethings fear that, if they do nothing for a year or two, house price inflation is now such that the door to a homeowning future might close on them forever. So they're rushing in. The lesson here is that the virus of desperate whirlygig househunting, that only way to make any money in the UK, is back - if it ever went away. It's another disaster in the making, akin to the abolition of dual Mortgage Income Tax Relief in the late 1980s, or the secondary banking crash of the early 1970s. No-one cares for now. If this turkey of a policy isn't put out of its misery quite soon, in two or three years voters are going to wake up and realise that they're on the hook for many tens of billions in private debt - while at the same time holding a student loan book that no-one wants. Reducing the deficit? Don't make me laugh.

So that's four valuable lessons in four mistakes - a four-for-four record. We don't recommend getting everything wrong all the time, mind, but a healthy dose of humility - and a good old dollop of analytical revision on the side - can help us see where our assumptions and prejudices end, and where reality begins. What's why we blog: to work things out as we go along; to play around with our ideas as they emerge; and to keep an honest record, in our case, of what we thought history (and History) might tell us about public policy.

In an age that's seeing many sound the death knell of the independent blog, it's not a bad set of aims. Stay tuned for more predictions - and more mistakes.

Thursday, 7 November 2013

Could rapid recovery turn into quick retreat?

Not the least of this blog's problems over recent months has been keeping up with the increasing rate of economic growth. We said that recovery would feel like a slog. Well, it still does - and it will for many years to come, if income growth is any indicator. But we thought that GDP figures would be pretty moderate as well, and they're probably going to turn out much better for 2013 and 2014 than anyone would have thought just a few short months ago.

But might this sudden burst of energy lead us into another quagmire? Businesses and consumers have curled up in so much fear and doubt, for so long, that they're now obviously going out and blowing some cash. That's great - for now. But the recovery is just as unbalanced, and just as patchy, as all the others that have led us right back to where we started since the end of the post-war 'golden age' in the oil and energy crisis of 1973. Because for all the talk of 'rebalancing' and 'export-driven growth', this incipient boom looks relatively unsustainable, at least over the medium term - just like all the rest.

That's going to cause a great big headache for the Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney. The Bank is also tapering off the monetary drip-feed the economy's been on while it was in the emergency room. Soon, and quite soon as these things are judged, it's going to have to start raising interest rates, despite his attempts to signal that he wants to hold out on that as long as possible. Current market sentiment says that this will happen late on in 2015, or perhaps in 2016. If it happens sooner - any time this side of a General Election - then the Government's much-trumpeted satisfaction at appearing to edge us back from the economic brink will evaporate pretty quickly. House prices are one reason. One reason voters increasinly sense that house price rises are a bad idea - despite (of course) wanting their own properties to spiral upwards in value - is that they know that the return of this particular fever pushes the next rung of the ladder - for both themselves and their children - ever further away. But consumers are in a lot of debt overall - which successive Osborne budgets have assumed will rise to offset the Government's own closed pockets. Small rises in interest rates might get us into quite a lot of trouble, quite quickly.

'Public Policy and the Past' offers you two historical parallels.

In 1955 Prime Minister Anthony Eden (above) and his Ministers were confident, purposeful and successful - riding a wave of economic decontrol and growth that put Eden back in Downing Street with an increased majority. Within a few months his Chancellor, Harold Macmillan, came back to the electorate with an Emergency Budget slamming on the brakes. Labour said: 'we told you so'. In 2004 Australia's Prime Minister, John Howard, won re-election boasting about his economic record - and the need to return his Liberal Party to office in order to keep rates low. Interest rates than rose, and rose, and rose - for years.

Both debacles did lasting damage to the idea of central economic management. Both might be replayed over the next few years. For returning to office on the back of a housing boom is not the smartest of plans - ask Conservatives with memories of what came after their 1987 landslide.

Monday, 4 November 2013

Universal Credit is dead: someone should have the courage to say so

The Government's reaction to the implosion of its sad - but predictable - Universal Credit debacle is instructive, for it fits exactly into the five stages of grief. First, there's shock. Then, there's denial. Then anger. Then bargaining, hoping against hope that you can put right what's gone wrong. Only then can come acceptance, when the bereaved can move on.

We've pretty much got towards the end of the denial stage now. We're getting to the 'anger' bit, where the well-intentioned but seriously-out-of-his depth Secretary of State lashes out at everybody, including his own civil servants. Government press releases may say that the scheme is moving forward, but everyone knows that it's about as over as New Labour or the Spice Girls - you might hear talk of them now and again, but no-one seriously thinks that they're going to make a comeback. Only one area has gone ahead with the recent 'roll-out' of the scheme's pilot phase, rather than the six planned even on a scaled-down timeframe; all the talk within Whitehall is about moving to an even more web-based system (one doesn't know whether to laugh or cry about this suggestion), or just ripping the whole thing up and starting again.

What that means is that the denial and the anger will pass - indeed, they already are. And then the bargaining will start up and then die away - the special pleading, the pain of admitting all the money you've poured into something has gone up in smoke. The attempts to salvage something - almost anything - from the wreck. Soon, there will come acceptance. After a General Election, there'll be a new government, in which case Universal Credit will get buried, or Iain Duncan Smith (above) himself will get moved on by a reinvigorated Prime Minister powerful enough to move a potential right-wing rebel to another job - or to the backbenches. He'd have loved to do that a year or so ago, of course, but Mr Duncan Smith resolutely refused to move - some tribute to his tenacity, if not to his insight.

Then whoever's in power can move on. Perhaps to address the total failure that is the Work Programme, nearly as much of a blot on the landscape as Universal Credit. Or maybe they'll be able to reconstruct the new Personal Independence Payments 'scheme' for disabled people so that its private assessors don't muck up so many of the cases. Those schemes have an odd curate's egg quality - they are good in parts - but the stench emanating from Universal Credit's corpse is blocking out just about every other idea in town.

Universal Credit was a good idea, in parts. But it turned out to be impossible to deliver, certainly over one or two Parliaments, and probably forever. Our society is just too complex, our computer technology too unwieldy, our frontline agencies too overwhelmed. We should have a funeral, do a bit of mourning, and then have a (sober and dignified) wake. Anything else is just throwing good money after bad.

Here's a memo for the Department of Work and Pensions: Universal Credit is dead. Time to dig it a hole and leave some flowers.

Friday, 1 November 2013

NHS scandals: they'll always be there somewhere

This weeks' official government report on National Health Service complaints makes for grim and depressing reading in places. It's long been time to face a fact that's been staring us in the face: some parts of Britain's NHS can be nasty, brutish, unfeeling and downright cruel. Lots of elderly patients end up herded around, while no-one really knows what to do with them. Lots of people are treated with unfeeling brusqueness, rudeness, nastiness and even malice. No-one can read the case studies from Mid-Staffordshire without shaking their head sadly at the injustice of it all.

Now there are lots of reasons for this. For one thing, cash-starved local authorities don't want to deal with ever-rising numbers of old people, leaving hospitals and doctors scratching their heads as to what to do with them. Hospitals are hardly the place for them, as there's often nothing physically wrong with them, at least acutely: but where are they to go?

The most important insight historians can lend to all this is that we've been here before. Again and again and again. We've had scandal after scandal - and revelation after revelation of poor treatment. Ely Hospital in 1967. South Ockendon in 1972, and Normansfield Hospital in 1976. All of the subsequent inquiries revealed that patients who could be ignored often were, relegated to backrooms and hidden wards, well out of sight of hospital and long-stay authorities who basically didn't want to hear about any problems.

What were the results? New governmental machinery. In the early- to mid-1970s, a Health Service Ombudsman, still there to this day - who could only look into the administrative side of these questions. New complaints mechanisms, forcing hospitals to take patients' views seriously. New legal rights. Citizens' and Patients' Charters. Commissions and Councils and Boards and 'Champions'. And so on - you can read about it all here, if you've a mind to track through an academic article about it. Where has it got us? Well, care is undoubtedly better overall now - partly because of much higher spending, and partly because NHS professionals have gradually got softer, friendlier and more patient-friendly over the years.

But none of the formal and governmental changes have eradicated poor treatment. Because they can't. It's a category error, like a visitor to Oxford asking where the university is while the buildings of its Colleges are all around him.

Only a cultural shift on the ground and in the wards can do that, along with many of the practical and admirable changes to training, treatment, complaints at institutional level, local management and constant vigilence that the Clwyd Report recommends. And an acceptance that, in such a huge organisation, poor treatment and downright nastiness will always be there somewhere. It can be driven down and into the corners, but it can't be eliminated altogether.

That's what the history of these scandals tells us - an insight that might make us worry about the very complex and impossible-to-manage NHS that is being born right now, under which no-one is quite sure who is responsible for exactly what. Will the future really be less risky than the past? No-one seems to know. More patients' rights, and some hard-headed practical reforms, say 'yes'; deep, grey and fuzzy administrative confusion says 'no'.

Watch this space.

Wednesday, 30 October 2013

Ed Miliband, the unhappy Prime Minister

Let's look ahead into the future, shall we? Enough of all that rambling around the past for today. Let's fast forward to 2016, by which time Ed Miliband might - just might - sit in No. 10 Downing Street. Regular readers will know that we think that's a big 'might', and that it's really too early too tell. One thing's for sure: he's going to have a heck of a task securing an overall majority big enough to last for a whole five-year Parliament.

But suppose he is there, having made so many good strategic calls for so long (think: News International), and he either governs as a minority government, or in coalition with the Liberal Democrats. What's the political scene likely to look like then?

Well, the historical precedents aren't all that encouraging. 'Public Policy and the Past' has continually compared Labour's leader to a much-maligned politician from yesteryear: Edward Heath, who defied terrible poll ratings, and the widespread perception that he was a 'born loser', to become Prime Minister in a shock election victory in 1970. He was another leader who no-one could imagine in No. 10, but who somehow held on doggedly until, against all the odds, he beat his more telegenic and more 'natural' opponent into submission.

But just look what happened to Heath. Continual states of emergency. Crisis after crisis. An eventual snap election - and defeat, after just three and a half years in the job.

No-one can say what will meet Mr Miliband if he does walk up Downing Street after an election victory in May 2015. The economy will almost certainly be recovering - though there will be a lot of pain emanating from interest rates either rising, or being about to rise. He will have been tempted to announce a referendum on the UK's membership of the European Union - which, if he loses, will almost certainly doom his premiership to unhappy defeat. His flagship energy price 'freeze' might have turned out to have been a good way of forcing prices up just before it started, promising further hikes at its end.

But here's one thing we can say - that possibility, of an unhappy and unpopular Miliband premiership, is all the more likely given the source of his apparently rather strong and resilient polling lead. Almost all of it comes from disaffected left-leaning Lib Dems who've abandoned their former allegiance, disgusted at 'their' party's alliance with the Conservatives. Where will they go if the Liberal Democrats elect a more left-wing leader after the next election - Tim Farron, perhaps, or Vince Cable? That's right - straight back from whence they came.

Leaving the new Labour Prime Minister way behind in the polls. So 'One Nation' Labourites might end up barricaded in No 10, perhaps, pulling out of Europe (against the wishes of the people of Scotland and Wales), and in a deep, deep electoral hole.

In politics, as in much else, the conclusion is: be careful what you wish for.

Monday, 28 October 2013

Modelling the next election: vast uncertainties remain

There's been a bit of a stir over recent days concerning a new statistical model of polling and popularity running up to the next election. Stephen Fisher, Lecturer in Politics at Oxford University, has published a new working paper using past polling trends to look at where we might get to in May 2015.

The results are pretty stunning, to be honest. Forget all that stuff about how impossible it is for the Conservatives to gain an overall majority because of the inbuilt bias of the electoral system, their non-existence north of Birmingham, the relative unpopularity of their sitting MPs, Labour's poll lead, and any number of other hurdles that have been thought to stand between David Cameron (above) and an overall majority.

No, Dr Fisher uses past data on governments' catch-ups over the last months of every modern Parliament, and the polls' record of overstating Labour support, to show that the Conservative Party is in fact pretty likely to win an overall majority. You can read the whole paper here, for free - it's only 19 pages long - and it repays a good long ponder.

Now there's a lot that's potentially going wrong with this analysis. One could equally point (more qualitatively) to historical parallels pointing the other way - showing that Labour aren't doing too badly on past form, and that it's very, very rare for incumbent governments to increase their vote shares. More narrowly, what one might call macro-approaches - that focus on the headline numbers - find it difficult to grapple with the internal dynamics of electoral switching. It's perfectly possible that Liberal Democrat switchers to Labour will stay put all the way up to election day, boosting the party's score from the low 30s predicted in this model to the mid-30s. No-one really knows. We're in uncharted waters. Sure, the numbers on single-party governments are strong, and other countries more used to coalitions back them up: the biggest governing party will indeed surge back into contention. But what if Labour's numbers don't sag in return? There seem to have been precious few switchers from Conservative to Labour, so those two processes are not mirror images of one another. It's a more parohical question that explains why Nick Clegg is trying to tack leftwards to get some of his 'lost' voters back. No-one knows whether he will succeed.

But this approach has the virtue of clarity. It has the advantage of showing us its workings - including the massive margins for error due to the assumed inaccuracies of past polls, to name but one uncertain element. It's an academic work that Dr Fisher is happy to take comments on, as you can see from the tenative nature of his draft and his careful and measured response to a tidal wave of comments. This blog has always been very, very sceptical that Labour will get as far as people have thought since the 'omnishambles Budget' of 2012, and there's been lots of recent evidence to back up that point. That party's progress in local elections, and in the polls, is anaemic, leaving the way open to a strong Conservative recovery - especially during a rapid economic upturn.

But saying that a Conservative majority is so likely - more likely than not - is a big, big punt. I'd like to say that you can tune in during May 2015 to see if regression analysis really does turn out to be a good guide to the future, but of course so much will have changed by then - so many events will have intervened - that it's not much of a test of whether the elements modelled here are the critical ones.

But it's a start - and it's better than a hunch, in anyone's language.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)