Sunday, 26 March 2017

No, Labour was not neck and neck with the Tories before the 'coup'

All political tribes live by myths and legends. Labour always talks about how Nye Bevan founded the National Health Service. The Conservatives put up paintings of Winston Churchill and Margaret Thatcher. There are probably few depths of bathetic silliness that such conjuring tricks cannot case in a warm glow. No doubt one day, Brexiteers will thrill around camp fires to the Tale of Two-Faced Boris and How He Slew His Friend. Or Gove the Brave, and How He Slew His Friend. Anyway, we digress.

The point is that it's perfectly natural for political movements, parties, even fragments of both or either, to tell themselves stories. They gee up the faithful. They encourage the doubters. Problems only really emerge when this process is either deliberately hothoused, like tulips in winter, by leaders who should know better. Or when those tales prevent the group seeing themselves, even for a moment, as they truly are or as others see them. Gods are fine. False gods? Not so much.

So it is with one of the most pernicious political myths of our time: that the UK Labour Party was 'neck-and-neck' with the Conservative Party (or might even have occasionally edged into the lead) in opinion polls running up to last year's European Union referendum. That there was then a deliberate 'coup' mounted by Labour MPs which so damaged Labour that the progress it was making - its emerging parity with the Government - was wiped out by a string of Shadow Cabinet and Front Bench resignations, a long leadership contest and a lot of bad, bad political blood. You can read this line as pushed by Left-wing pressure group Momentum here. You can read the reported remarks of Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell on the matter here. Here's a good example of a left-wing blog (from last year) saying the same thing. Here's Paul Mason from last summer, saying that Labour and the Conservatives were 'neck and neck' then.

There's one main glaring problem with this view: it isn't true. Labour was certainly never ahead, and the most respected experts in the field have baldly judged that '[the] frequent claims that Labour were equal to (or even ahead of) the Tories before Labour’s leadership troubles erupted... [are] disingenuous... at best, and seem... to rest wholly upon cherry-picking individual polls'.

Now let's leave aside the vexed question of the word 'coup' here. Probably there were some elements of a 'coup' about the whole thing. Quite a lot of Labour MPs had been waiting for some way to overturn the party's new-old dispensation, and in the immediate aftermath of the Remain campaign's failure thought they had found it. But the 'riot of despair' that overtook the Parliamentary Labour Party had so, so many more elements to it, reaching all the way from the Leftest of the Soft Left to the hardest of Blairites, that 'coup' is a vastly inadequate and misleading term for it. Maybe we'll write about that at more length someday.

Let's focus instead on the polling numbers, and the logic behind them. First, take a look at the chart above. This is all the polling from the calendar year 2016, showing the main two parties' ratings on a six-poll rolling average. The first thing we see? The Labour line never touched the Conservative line. They were not 'neck-and-neck'. The reason we use the average from many polls is that polls are subject to so-called 'normal' error: if two parties were truly about as popular as one another, you would expect quite a few showing the red team three points ahead, and about the same number showing the blue team three points up, as well as quite a few in between and many others showing a dead heat. Did we ever, ever see that? No, we did not.

There were only ever three polls that showed Labour ahead of the Conservatives. These were all reported by the polling company YouGov, on 17 March, 12 April and 26 April. They showed Labour ahead by one point, and then twice by three points. There was one more poll that showed the two parties dead level, carried out by Survation for The Mail on Sunday and published on 25 June. That's it. All the other polls, for the whole of the first half of the year leading up to Hilary Benn's sacking in the early hours of 26 June, showed Labour behind. That's simply not the pattern you'd see if parties were truly 'neck-and-neck'. Case closed.

Case-even-more-closed, point one: Labour's slide did not begin on 26 June. Rather, it had begun more than two and a half months earlier. Labour's poll rating 'peaked' at an average of 33.7% on 1 April: it had already fallen to 31.2% by 26 June. The smallest average Conservative lead was one per cent, registered on 12 April: this had already opened up slightly, to 2.7%, by the time the Shadow Cabinet began to disintegrate in the immediate aftermath of the EU referendum. Not only that, but this was but one more passage in Labour's medium-term collapse, having peaked at nearly 43% in the immediate wake of George Osborne's catastrophic 'Omnishambles Budget' during the spring of 2012. Their average now? About 27%, on a glidepath that hasn't seen great big dramatic falls in support, but a slow, gradual, painful retreat that suggests structural, not directly political (and certainly not high political) causes.

Cause-even-more-closed, point two: yes, Labour did get quite near to the Conservatives in the spring (not the summer) of 2016. But that was not due to any great surge in enthusiasm for socialism, Parliamentary or otherwise. The reason we've just put the word 'peaked' in quotation marks is that 33.7% was an absolutely pathetic rating for Britain's main Opposition, as we noted at the time. Such a polling number always suggested, on a historical basis and using the very best numbers we could scratch up, a pretty bad defeat. That closer gap that we see from late March to late June 2016? That looks rather like a quick Conservative tumble from around 38% on the eve of Mr Osborne's 2016 Budget (delivered on 16 March) to 33.5% at the moment of the Brexit vote. It looks, in that context, less like a surge in Labour's support, which went up by less than two points between the period immediately preceding the Budget to its molehill-like 'peak' on 1 April.

None of which should be a surprise. Because what had happened in the interim? Oh, just the matter of the most popular Conservative politician in the country coming out against the Conservative Prime Minister's flagship policy on Europe. And the Chancellor's Budget cutting benefits for disabled people, causing the Work and Pensions Secretary to resign. And the Conservative Party (including the Cabinet itself) tearing itself apart over Brexit. Oh, and the Prime Minister admitting that he'd used a tax haven for a family inheritance. That's all. And the Conservatives, by the way, still couldn't throw away their polling lead.

So those posts on Facebook that you see, saying that 'if only it hadn't been for the coup, we'd have been okay'? Those Twitter eggs that pop up telling you that Labour were toe-to-toe with the Tories in the spring of 2016? They are reflecting densely-woven webs of spin shot out by long-serving politicians who should know better, and they are telling not stories but fairytales - all the better not to see themselves with. Actual history, written by actual historians, says something very different.

Yes, we're wasting our breath - we usually are - but Labour was not, ever, 'neck-and-neck with the Tories before the coup'. If anyone says they were, you can link to this page. You can paste up this blogpost. You can quote these figures. You can send them to us. Don't mention it. It's a public service.

Sunday, 19 March 2017

British social democracy in crisis

Most politics commentary is impoverished in two ways. It is geographically parochial and temporally anachronistic. It can see neither the big view nor the long view. It is obsessed with the latest rivalries, the newest personalities, the most novel ups and downs. So the Labour Party's deep travails focus on the struggle between its MPs and leader. On the latest reshufflings within constituency parties or in the National Executive Committee. Whatever today's latest bit of shouting involves.

But zoom back, and Labour is actually in the grip of an acute crisis within social democracy itself. And these apparently-insoluble dilemmas are not happening in Britain alone. The Greek Socialists were wiped out by that country's financial crisis. The Dutch Labour Party took a tremendous beating last week. The French Socialists are about to lose the presidency, either to a charismatic centrist or to the far right. At its base, social democratic coalitions have always tried to reach out to everyone (above) - professional people, working people, the young, the old, men and women, all nations within a state - because social progress is thought to benefit everyone. More recently, this has increasingly come to mean finding the glue that will stick the instincts of liberal urban dwellers to more socially conservative voters in small and medium-sized towns. For a number of reasons - large-scale immigration, rapid cultural change, a yawning age gap in the attitudes of the generations, stagnating wages, you name it - those links are coming apart. It may not be possible to hold them together for much longer.

That's just the start of British social democracy's many crises. The Scottish National Party has routed it in its historic fastnesses of urban Scotland. The English nationalism encoded within the United Kingdom Independence Party has tempted away many voters in England's provinces. The rise of Sinn Fein in Northern Ireland is another challenge that the entire British state - and its generally redistributive alliance of four unlikely economic partners - is struggling to meet. Okay, the Welsh Nationalists of Plaid Cymru have made but little progress recently (opens as PDF), but Wales is the only part of the UK where political nationalism seems still relatively weak. If it does not serve as a lobby for the poorest parts of the UK - Northern Ireland, say, South Wales, or the Eastern fringes of Glasgow - it is far from clear that Labour has any mission anyway. Want to see how a Labour Party does when all politics is a struggle within and between different visions of 'the nation'? Look no further than the Republic of Ireland, where it has only ever come third.

Labour is also faced with a terrible, tragic dilemma over Brexit, not so much because Labour constituencies were particularly divided between Remain and Leave (Conservative seats were nearly as split), but because so many of the voters Labour has now were Remain, and so many they need in the future were for Leave. Last but not least, Labour has essentially evolved into two parties, which seem to know as little of one another as if they are two nations. The first, made up of long-standing members who joined before 2015, are loyal to a certain idea of the party as a receptacle for progressive, reforming, legislative hopes for incremental change. They want to make the country better gradually. The second, constituted mostly of more recent members, hopes to totally remake at least the party - and, perhaps in some hopeful future, Britain itself - in the heat of a charismatic tilt at social justice at home and peace abroad. They should probably split. They can't, because the electoral system means that they would both suffer more than if they stay together. So both sides have to tolerate a flatshare from hell. There really does now seem little to bind them together. The great trade unions, and in particular the mega-union Unite, would once have formed one bridge across which ideas could cross: but with Unite in the hands of one side of Labour's ongoing civil war, that now seems impossible.

Keep in mind that parties die. Remember that Britain entered the twentieth century with a great, radical, reforming and established party to the left of its centre: the Liberal Party that had done so much to forge Britain's route to modernity itself. It renewed itself during a 'New' Liberal phase of novel ideas about social reform in the run-up to holding power between 1905 and 1916. It struggled to reconcile the competing claims of Irish nationalism and English conservatism. It puzzled over Scottish land reform and the future of the Welsh church. These constitutional issues in turn drained its energies from facing the economic and social questions: forces quietly starting to break up the base of its support among both suburban householders and the urban working classes.

There are troubling echoes there for the way in which 'New' Labour in Opposition and in power found itself increasingly uncertain about the correct balance of forces within the political system, and how its record in power gradually came to seem inimical to sustaining a united, widely appealing programme. It did take the First World War to really sweep the Liberals away, for they had done creditably up until then at combining social reform with rearmament, and economic change with constitutional reform. Reconciling personal liberty with the needs of the state during the age of total war proved to be beyond them. Complex as Brexit will be, the state faces nothing like the challenge of 1914 now.

In a way, though, that's not the point. The lesson is: events can just conspire against you. The atmosphere can change. Sometimes, the work you've done - the work any group or party was designed to do - is over. At the risk of over-determining, any movement can surmount one or two crises. But there's just too many coming at Labour, from too many directions, to see this as anything other than a perfect storm that will leave it out of power for a very, very long time, if not crippled on a semi-permanent basis.

Okay, you could try to speak in a new way (for Labour) - in the language real people use every day, rather than the cod-outraged sub-Marxian jargon than the party's press office uses these days, full of 'revolving doors', 'elites' and 'establishments' that properly reside in the 1960s and 1970s, if they ever existed at all. You might be able to find an answer to the rise of the United Kingdom's many nationalisms by splitting into say, English, Welsh and Scottish Labours - and having your own policies in each jurisdiction. You could meet the challenge of Brexit by moving more strongly in one direction, just as the Conservatives have - though that would need a touch more discipline and self-awareness than all wings of the Labour Party have been demonstrating in recent months. Maybe you could broker a deal between the Soft Left and the Old Right, excluding Blairite and Momentumite extremes from policy-making and administration. Perhaps you could really, really clamp down on the abuse and fury that rains down on even the meekest on social media - all the better to start looking outwards, rather than at the party's own navel.

But at the moment Labour is in more lines of fire than you'd find in a Tarantino film. It's trying and failing to deal with triumphant nationalism, the overarching crisis of Brexit, the increasing gap between social democrats and the blue-collar working people they've always relied on, cities and exurbs that are drifting apart, the bitter and probably irrevocable split in the party between the 40% of more long-standing members and the 60% who've just arrived (or come back), the development of tight-knit but cramped social media communities who are impervious to news or views from outside their own moral universe.

It's too much. It can't be done. We've looked at the data many times (and we'll be taking another in-depth look again next month). That's bad enough. But when you take a really cold look at the structural, intellectual and political elements - when analysis is pressed into use, to explain the report of mere numbers - the picture looks even darker. The situation for reformist social democracy - the rock on which the Labour Party historically stands - is bleaker than it has been at any point since the Second World War. Parties mostly shy away from the brink. They usually find some way to come back. It took just seven years for the Conservatives to recover from the chaos engulfing them under Iain Duncan Smith. But as the 'New' Liberal example shows, sometimes political parties are pitched into extinction. Labour is hesitating between the two options. Its many crises do not make for optimism.

Sunday, 12 March 2017

Silly history, childish policy

Anyone who really knows a subject winces when Ministers talk about it. Internet security? Here's a Snooper's Charter that will build up a great big database hackers can steal. Higher Education? Here's some really tight and stupid limits on the numbers of (fee paying) foreign students you can take. Oh, and by the way, here's some ridiculous metrics of teaching quality that'll never work, and don't tell you much about teaching anyway. Austerity? Told over and over and over again that this won't close the deficit on the timescale the Government pretends to believe it will, Ministers go on reducing current spending. Early on in their ill-fated drive towards a much smaller state, they even pruned back productive capital expenditure at a time of very low interest rates. And so on.

It's the same when professional historians look at what politicians say about the past. In fact, it's even worse, because Ministers when they blunder into this sphere don't have civil servants to advise or constrain them. They don't have a load of briefing notes, or binders full of reports, keeping them at least in the neighbourhood of the straight and narrow. They show off their preconceptions and prejudices, sometimes for good, but often demonstrating a very dispiriting lack of grip on reality itself.

The latest example of this is one of the most illuminating: Trade Secretary Liam Fox (above) and his apparent desire to forge the Commonwealth into a sort of nostalgic new-old trading bloc to replace the European Union. That all looks a bit desperate in policy terms, actually, and not only because it comes from Mr Fox, no stranger to less-than-edifying controversy and disgrace himself. For one thing, such a strategy would give Commonwealth nations such as Australia and India a gold-plated opportunity to run the board on the Brits if the UK does look likely to crash out of the EU without a deal. The amount of trade that Britain does with them already is also puny compared to links with its European neighbours. And many countries - particularly poorer Commonwealth nations - are not even that keen on what sceptical civil servants have apparently dubbed 'Empire 2.0'. Why should they help Britain sell them a load of cars in return for slightly better terms on Britain's commodity imports? There would seem to be no better way for them to worsen their terms of trade.

Mr Fox says that he doesn't use the term 'Empire 2.0', and nor does he want civil servants to use it. That would apparently belittle Britain's global role, rather than its post-Imperial identity. He has form in just this sphere, though, having tweeted in 2016 that 'the United Kingdom is one of the few countries in the European Union that does not need to bury its 20th century history'. It's a statement that will lead almost all professional, responsible and reflective historians to scratch their heads and say: er, we're not sure that's quite right. For British Ministers to claim that they don't have anything that they might be embarrassed about, or which many people might choose to forget, is a frankly bizarre assertion.

Let's tread carefully. Condemning and judging, rather than understanding, risks the fatal historical error of anachronism. Your analysis is not going to get very far if you just say how terrible it all was. And Britain's Empire was a complicated thing - a huge, multifarious, many-faced enterprise that lasted hundreds of years. So it's important to go lightly here. No doubt it was better to be governed by the British than (for instance) the Belgians in the Congo. Of course British administrators and settlers became less rapacious as the idea of a 'liberal empire', preparing new states for independence, gained a hold in the twentieth century - though we still wouldn't have recommended getting in their way. During the 1950s, many Kenyans found to their cost just how nasty the sting that remained in the British tail could be - a dark and brutal story that was then covered up for many decades, until historians dragged it into the light.

The final acts of the British Empire also became apparently self-mitigating acts of abrogation and heroism in the British mindset - perhaps one reason why the British public still perceive the Empire-Commonwealth through a warm glow of nostalgia and regret for its passing. The 'Spitfire Summer', in which Britain 'stood alone', in the end seemed for many to wash off the guilt of Empire itself. John Maynard Keynes said famously that 'we saved ourselves, and we helped save the world'. There's a lot of truth to that. But it's also more than important to note that it was the British Empire that 'stood alone', not just the peoples of the United Kingdom. Caribbean airmen fighting in the skies above the South of England; Indian soldiers in North Africa; Australian infantrymen in Burma and at the fall of Singapore: they were taking the brunt of the disaster just as much as were the British themselves.

So was the British Empire really a free-trading group of complementary peoples? Is Britain really unique among Europeans because it 'does not need to bury its 20th century history'? No. No-one should be burying any history, least of all the British. The Amritsar Massacre of 1919, the ferocious attempt to suppress opposition in what became the Irish Free State, the catastrophic Partition of the British Indian Empire, the nuclear testing programme in Australia, the Suez debacle of 1956 - none of them covered anyone in glory, that's for sure. Each was by turns a toxic mix of the violent, the destructive, the negligent and the chaotic. Each speaks to Imperialism's deeply interwoven history of arrogance, greed and hatred.

There's a lot of wishful thinking about these days. According to Mrs Thatcher's biographer Charles Moore, Britain might now become a grounded semi-idyll rather like The Shire in J.R.R. Tolkein's The Lord of the Rings - an honest place of attachment and belonging, where no doubt yeoman farmers labour manfully in the service of a rightful order. Melanie Phillips has brought her trademark historical insight to the party by claiming that Britain is a 'real' nation in a way that, say, the Republic of Ireland is not. We should have the courage to call this out for what it is: baloney. It's a comforting warm bath of half-facts and thinly-remembered pasts that never did exist and never could have existed.

It's not just an academic argument. Good history is essential to evidence-based public policy. Our view of the past tells us what we think of the present, and by extension the future. If we really start to believe that Britain once ruled over happy groups of merchant adventurers, a band of fellow-feeling settlers and subject peoples set on their way to liberty, we will make a grave blunder. We might, in terms of our broad preconceptions, start to forget the real suffering that the British have inflicted on the world - something to weigh alongside all the good that they have done, whenever and wherever we write about it all.

But there's also a more acute danger - a pressing one that's relevant to the Government's choices right now. That is to see the victors at Blenheim and Waterloo, the people who lived under first a Dutch and then a German monarchy, the land with French law and language, the people who defeated European fascism and framed the European Convention on Human Rights, as a power that has always engaged in Empire rather than the continent they must still call home. That has never been an adequate picture of British history. Today, more than ever, it should not be meekly accepted just because some amateur politicians and commentators want to use the past for their own ends.

Monday, 6 March 2017

More historical context on Stoke and Copeland

One thing we know about public numbers is that they have

to be built up via art and artistry, as well as science. You don’t just go and capture them

in the wild, like they’re some form of easily-displayed and gawp-inducing new

specimen for the zoo. The next thing we know? Context is all. It’s the same in

every field. How big is that exoplanet? What does that mean in comparison to

the Earth? How big is the sun it’s orbiting? What might that mean for its

atmosphere, the potential for water on the surface, the likelihood of life?

One context is historical. Okay, economic growth looks

like it’s enough to keep unemployment low, but how fast or slow is it against

the longer-term averages? The usual level of growth since the Great Disruption of

2007-2008? The mean scores since the Second World War? Only then can you know

what you’re really looking at.

That’s why we look at election results (and opinion

polls) in the same way. It’s all very well being quite some way ahead, as

Labour were in the last Parliament, but what does that mean? We wasted our breath then pointing out that Labour had to rise quite a bit further before

they looked likely to win a General Election, and we probably still are, but

it’s worth a go. We’ll be returning to this theme in April, when we take our regular

look at how the Government and the Opposition are doing when measured against

the standards of the modern era (which roughly means since about 1970). But for

now, it might help to take yet another look at the Copeland and Stoke Central

byelections in a wider, longer – and statistically marginal, rather than binary

– context.

Now, stop us if you’ve heard this before. We know that we looked last time at just how bad these two results were for a serving

Opposition. There’s really been nothing like Copeland, especially, since on

some measures the nineteenth century. You could fill a page with words like

‘appalling’, ‘disastrous’, ‘humiliating’ and ‘catastrophic’. That’d be about the

measure of it. But that doesn’t seem all that helpful, to be honest. Anyone can

write a faux-Biblical and mock-ominous paragraph of doom. Believe us: we have.

But what is the exact scale and scope of Labour’s byelection performance, both

in Stoke and Copeland, and more broadly over the past couple of years?

Here's where we can deploy at least some sense of

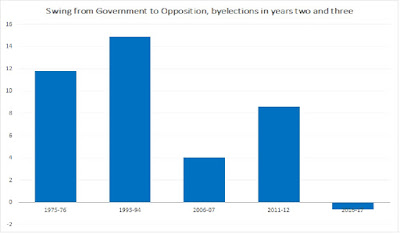

statistical clarity. This time, and for the chart above, we’ve looked at

various Oppositions’ byelection performances over the second and third calendar years of each Parliament. First, we’ve looked at the performance of those Oppositions that

were later successful in winning power: Mr Heath and Mrs Thatcher’s

Conservatives in 1974-79, John Smith and Tony Blair’s Labour in 1992-97, and

David Cameron’s Conservatives from 2005 to 2010. As a comparator, we’ve included the

byelection performance of Ed Miliband’s Labour in 2010-15: an Opposition that

appeared to be doing okay (but no better) in byelections at this point in the cycle, and was

competitive in the opinion polls, but which ultimately fell short when it came

to the crunch of a real General Election.

What do we find? Well, successful Oppositions should be hoping for big, big movements towards them. That’s not much of a surprise, but it’s nice to see it

confirmed in the actual numbers. Both Heath and Thatcher, and Smith and Blair,

were posting swings from the main governing party of over ten per cent – of

11.8% in the first case, and a spectacular 14.9% in the second. David Cameron

was getting some sort of swing at the same stage of the electoral cycle we’re

at now (approaching the halfway point), but it was much lower – at about 4%. It

won’t escape your attention, either, that the scale of those swings bore quite

a strong relationship to the subsequent full-scale election. Mrs Thatcher won a

modest but workable majority in 1979; Tony Blair triumphed in 1997, gaining

Labour’s biggest-ever majority in a remarkable landslide; David Cameron, who

wasn’t doing quite so well at this stage in terms of Westminster byelections,

had to settle for a coalition with the Liberal Democrats. At some point we’ll

try to write a full-scale piece about the formal relationship between these numbers and

General Election vote shares since 1945 (or encourage someone else to do it),

but for now we can just say that the bigger the swing at this point, the more

likely subsequent electoral success seems.

Clearly that doesn’t always hold. Ed Miliband was doing

better in 2011-12 than Mr Cameron was in 2006-07. You can enter all sorts of

caveats here. There were fewer byelections in 2006-07 than during 2011-12: there were just five such

contests in the former period, compared to the twelve held during Mr Miliband's second and third years as Leader of the Opposition. Three out of

those five battles took place on very unfertile ground for the Conservatives (Dunfermiline and West Fife, Blaenau Gwent and

Sedgefield). Even so, we should note that there’s clearly only a rough and

ready relationship between doing well in these elections, and then going on to

form a government.

So these comparisons aren’t perfect, or

always tightly predictive. However, and given Labour’s performance recently,

what they are is very suggestive. Over 2016 and 2017, there have so far been

eight Westminster byelections. and the Opposition has on average made no progress

at all against the Government. Indeed, they have gone backwards: there has been

a very small (0.65%) swing towards the Conservative Party. And things have got

a lot worse since Britain voted to leave the European Union. The swing to the

Conservatives is 3.9% since the summer of 2016, and an average of 4.35% in

Copeland and Stoke. The evidence is that Labour’s performance in these

byelections is steadily getting worse – just as its poll ratings have been

slowing deflating since the April of 2016. But it was anaemic, and deeply

concerning, long before that. The only place where Labour have even come close

to matching what remember was only its average performance under Ed Miliband is Tooting in June 2016,

where they achieved a swing of 7.25% towards them. Since we know from polling

and last year’s Mayoral election that Labour’s support has not retreated in the capital to the extent it might have done elsewhere, that’s yet another confirmation of everything else we thought

we knew from what data we have.

No Opposition in the modern age has

taken power without getting quite a swing towards them in Westminster

byelections held at this stage of the Parliament. No party has fully and

without help replaced another in Downing Street with a move towards it that was

below double digits. At the moment, the tide is flowing quickly in the other direction – just about as quickly, actually, as it was towards David Cameron in

2006-07. Don’t trust polls? Trust real votes. The picture is pitch black and still

darkening for Prime Minister Theresa May’s opponents, and they know it.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)